Greece’s map for predicting wildfires is anachronistic and inadequate

An investigation of MIIR

By Kostas Zafeiropoulos

4/8/2023

Photo: The spread of the deadly Mati fire in 2018, as it was simulated by the IRIS 2.0 rapid response forecast system.- Source: Meteo.gr, 2021

In the space of just 13 days in July 2023, 470,000 acres of Greek forest were burnt to ashes. Greece’s state machinery is proving inadequate to deal with extreme weather phenomena. In Rhodes, 15% of the entire island was ravaged in the worst fire in decades. From 1 January to 1 August 2023, according to the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS), a total of 550,000 hectares were burnt in the 22 largest forest fires. This is more than four times the average amount of land burnt in the years 2006-2022.

In an earlier survey by MIIR in collaboration with WWF on the economics of forest-fire protection we showed that, for the period 2016-2020, only 16.05% of public funds for fire protection were spent on fire prevention. Most, 83.95%, was spent on fire suppression. This ratio has not changed significantly since then: the Greek state has continued to invest in suppression instead of prevention. Another major problem can be found in the state’s inadequate use of scientific data during the fire season.

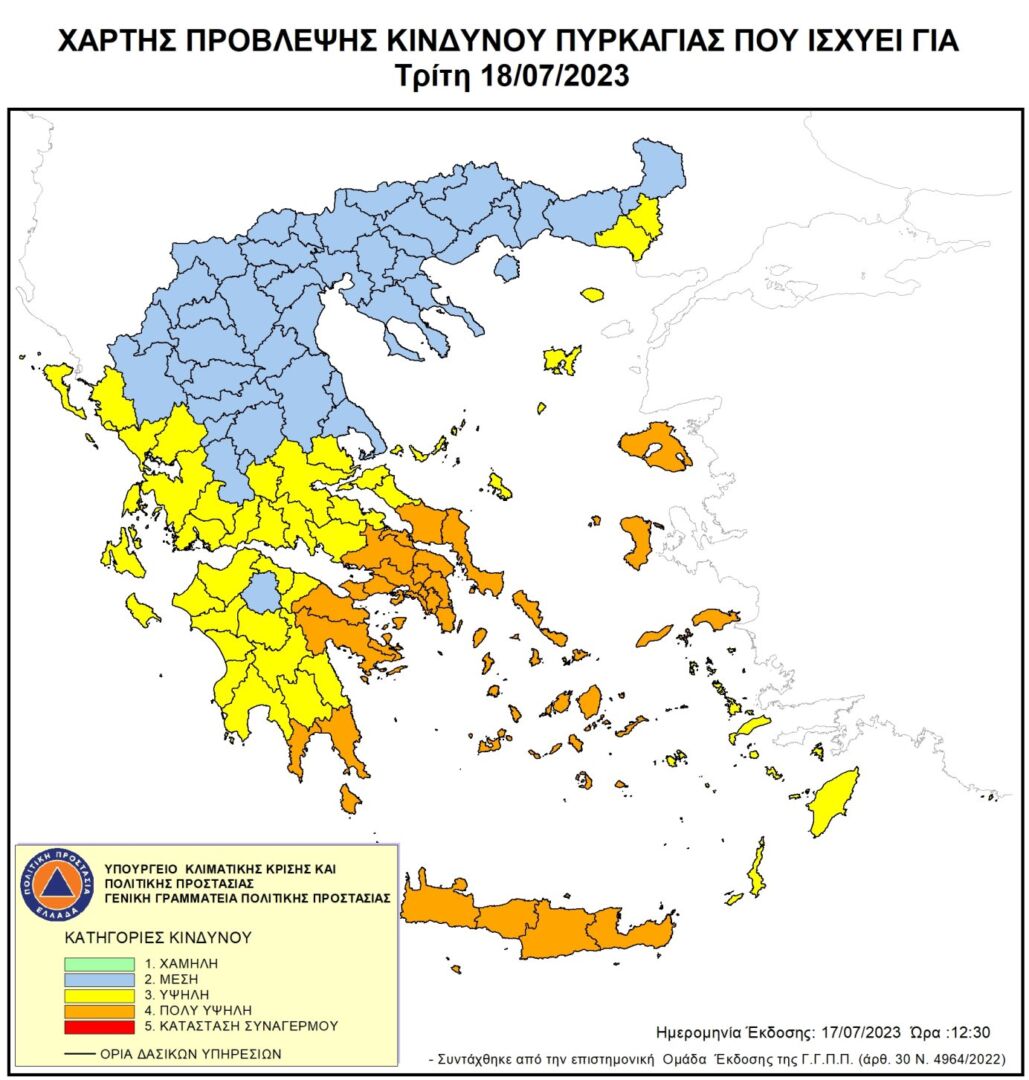

A typical case is the notorious fire-risk forecast map, which is published daily at 12.30pm by the General Secretariat of Civil Protection, in a rather opaque manner. This map is reproduced by all the media and forms the basis of the national Fire Service’s operational planning. It started to be used in 2003 and is published daily from 1 June to 31 October each year, under the purview of the Civil Protection. However, for twenty years now, none of the experts has known exactly what data and scientific methodology is used to produce this map.

Photo: The Civil Protection’s fire risk forecast map for 18 July, the day the huge fire broke out in Rhodes. The risk level for the island and the rest of the Dodecanese region was placed in the middle of the scale, which is classified as “high”. – Source: Ministry of Climate and Civil Protection.

Intuition instead of data

“The map circulated by the Civil Protection, whose derivation we do not know, has no scientific sources, does not mention how the different categories are regulated, nor what it takes into account. My assessment is that the Civil Protection map comes out on the basis of simple intuition,” says Kostas Lagovardos, meteorologist and research director at the National Observatory of Athens.

The map’s first drawback, according to experts, is this lack of clarity about the exact scientific data used.

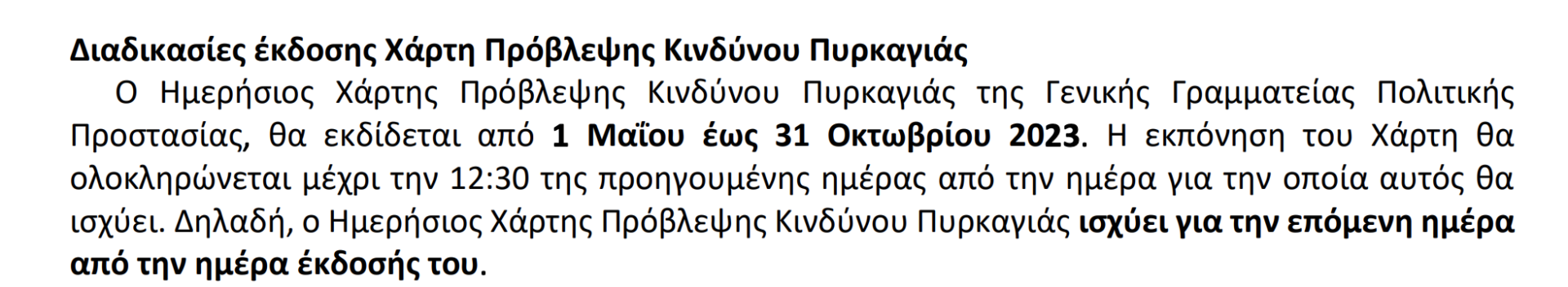

The main problem, however, is that it is issued once a day (covering the next 24 hours) and so does not take into account the very frequent variations in weather conditions during the day. As confirmed in a circular of the Civil Protection, once the map is issued, it does not change in any way.

Photo: Excerpt from the Circular of the Ministry of Climate Crisis and Civil Protection on the issue

daily Fire Risk Prediction Map from the G.G.P.P. during the 2023 fire season.

Andrianos Gourbatsis, a lieutenant-general and former deputy chief of the Fire Service, explains: “This is a big mistake, because the meteorological data may get worse, it may get better, so how is it possible not to change the map? What if you issue a hazard index of 3 for tomorrow, and suddenly in the evening the wind comes in, the temperature drops and the hazard becomes 5? This is the biggest disadvantage. There is another issue: the people who issue the map every noon then proceed to get off work, they go home, they do not follow the meteorological data of the National Weather Service.”

Another shortcoming of the map is that it treats entire regions, prefectures and other subdivisions as single units, without taking into account their different climatic conditions as pertaining to fire.

Kostas Lagovardos explains: “On the map, every region has one colour, which has no bearing on reality. For example, the winds in southern Crete are much stronger and have no relation to the winds in northern Crete. So in heavy weather, which is a typical summer event, you have a huge difference in the pyro-meteorological situation within the same prefecture. You can’t have entire regions having the same level of alert everywhere.” This means a dispersal of the firefighting forces on the ground, with all the devastation that might result.

After all, this fire-risk map is directly connected to the operational plan for fighting fires.

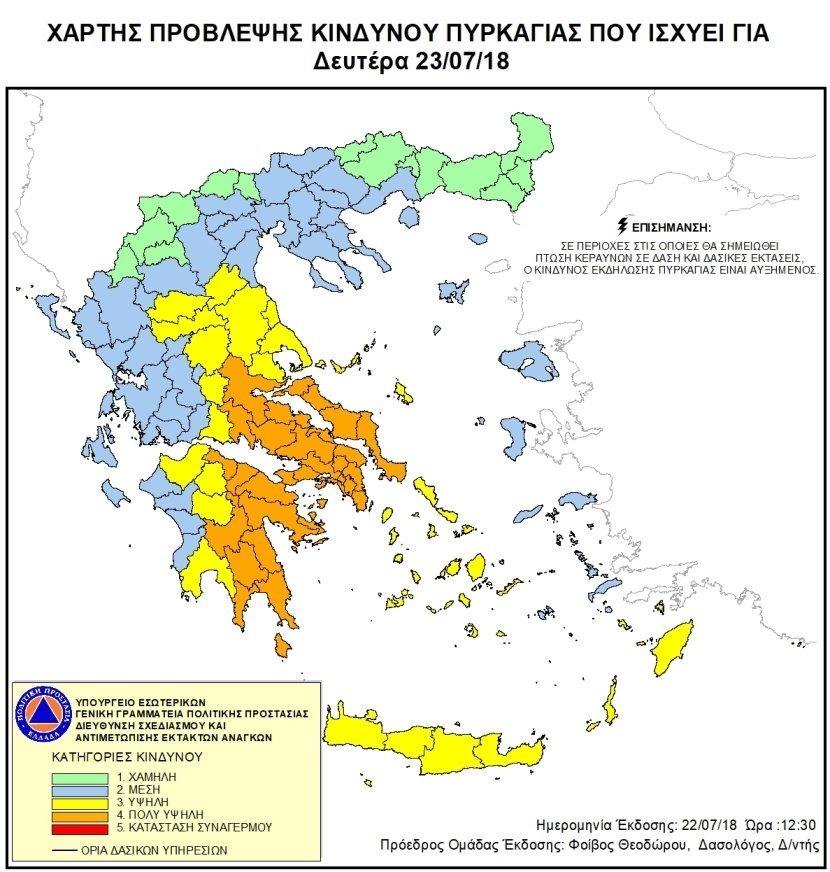

In the catastrophic fire in Mati in 2008 (which killed 102 people), the fire-risk map indicated a level of 4 (the maximum is 5). Andrianos Gourbatsis, who is also knowledgeable about the fires in Mati (2018) and Varibobi (2021), elaborates: “The conditions were for an index of 5 at the time. With an index of 4, the Fire Service’s state of readiness was not the maximum. If it had been 5, the Fire Service would have brought out an additional 25 units, from the 86 it had, while more fire stations would have been staffed for more hours, i.e. people would have been more ready.”

The Civil Protection’s Fire Risk Forecast Map for 23 July 2018, the day the deadly fire broke out in Mati. Source: Ministry of Climate and Civil Protection.

In the catastrophic fire in Mati in 2008 (which killed 102 people), the fire-risk map indicated a level of 4 (the maximum is 5). Andrianos Gourbatsis, who is also knowledgeable about the fires in Mati (2018) and Varibobi (2021), elaborates: “The conditions were for an index of 5 at the time. With an index of 4, the Fire Service’s state of readiness was not the maximum. If it had been 5, the Fire Service would have brought out an additional 25 units, from the 86 it had, while more fire stations would have been staffed for more hours, i.e. people would have been more ready.”

When there is a category 4 or 5 risk in an area, the Fire Service must effect an aerial surveillance. If the patrol sees a fire, the Fire Service must intervene immediately. In the catastrophic fire in Varibobi in the summer of 2021, two Air-Tractors were patrolling the area from 11 am because of the danger index. Gourbatsis notes that “Mr Hardalias [deputy minister for civil protection at the time] gave an order for them to land at 13.00 and stand by ‘if needed’. The fire in Varypobi subsequently broke out a kilometre from the airport. The planes had been on standby for 20 minutes, and precious time was lost as they got back in the air.”

Civil Protection ignoring the National Observatory

Phoebus Theodorou was for years the person who signed off on the maps of the General Secretariat of Civil Protection. He is a forester, not a meteorologist. He retired some time ago, but according to MIIR’s information, he remains an advisor to the Ministry of Climate and Civil Protection and continues to be involved in the publication of the disputed map. It is no longer approved by him, but by the scientific team at the Civil Protection secretariat. The individuals who make up this team have not been identified.

Andrianos Gourbatsis argues that “Civil Protection is stuck with the charter that was issued in 1995 when the service started. A lot of things need to change. On the weekend, these Civil Protection officials are at home, yet they still issue a map. This is not serious. They check EFFIS data every day, they see where it ‘blackens’ and issue the map accordingly”. Since the 2000s, as deputy chief of the Greek fire service, he has been asking politicians to have the map issued instead by Greece’s meteorological agency, EMY. His suggestion has gone unheeded and EMY is now doing even less work than before. It used to issue a special daily map of the conditions in the burnt areas.

Phoebus Theodorou, the official formerly in charge of issuing the Civil Protection maps, has claimed (GrTimes.gr, 08/06/2021) that they are based on the Forest Fire Weather Index (FFWI) of the Canadian Forest Service, as well as other geographic information systems and software. The National Observatory of Athens refutes this assertion. Kostas Lagovardos, at the Observatory, is categoric: “It can’t be using the Canadian index, because if it did, it would produce the results that we do. Southern and northern Crete would almost never have the same hazard index when they have different scores of 4 and 5 on the Beaufort scale.”

We contacted Phoebus Theodorou in order to answer questions about this, but to no avail. In addition, we sent written questions to the General Secretariat of Civil Protection but received no response by the time this article was published.

At the moment, the most authoritative daily fire-risk map in Greece seems to be that of the National Observatory of Athens. It is based on the Canadian pyro-meteorological index and takes into account temperature, humidity, wind, drought, how many days it has not rained, in order to produce a number to quantify risk. It offers a better analysis than the corresponding Civil Protection map, since it reaches a 2×2 km level of resolution in each region of the country. However, the fire service – at least officially – bases its planning on the Civil Protection map.

Vassiliki Kotroni, director of research at the Athens Observatory, comments that “we don’t know how the Observatory data is used by the General Secretariat for Civil Protection. We do know that our weather monitoring uses a network of 550 weather stations that we operate throughout the country. Since this data is freely available, it is possible that the Civil Protection monitors our stations. But this is not based on a memorandum of understanding, on any formalised system that would oblige us to operate in a certain way. We are doing this without any obligations. In a properly organised country, things should be a little different.”

Dr Kotroni is the scientific director of the Observatory’s Meteo team, which has pioneered a mechanism to forecast the spread of fires. Called IRIS, the system is innovative at both Greek and European levels. It aims to facilitate rapid responses to active forest fires. Knowing the location and time of the start of a fire, the system can, within 20 minutes, provide a forecast of how the fire front will develop over the next few hours. Within half an hour, it can provide a forecast for the next 24 hours. The system takes into account both the meteorology and the changing weather conditions caused by the fire itself. In 2019-2020 it was successfully used in cooperation with the Civil Protection and the Fire Service in over 200 forest fires. However, for two years now, explains Dr Kotroni, “for reasons we do not know, the cooperation has faded away, and unfortunately since 2021 it has not been sought by the Civil Protection or the Fire Service”.

Although it was available, IRIS was not used during the major fires in Varibobi and Evia in 2021. In a post after the fire in Varibobi, Meteo.gr stressed that it had carried out an “ex-post forecast”, adding that “the forecast that IRIS 2.0 could have provided operationally if it had been requested is very close to the actual spread of the fire”. Today, the IRIS system is still being developed with the Athens Observatory’s own resources, without any involvement of the state. It was not used by the Civil Protection even during the catastrophic fires of July this year.

The video shows the spread of the Varybompi forest fire in 2021, as simulated vy the IRIS 2.0 rapid forecasting system. Source: Meteo.gr

This material is published in the context of the “FIRE-RES” project co-funded by the European Union (EU). The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project. Responsibility for the content lies solely with EDJNet. Go to the FIRE-RES page