Greece's shaky "green" investments

Are resources from Europe’s post-pandemic recovery plan for the green transition being allocated wisely?

The decisions of Greece and 10 other countries come under the microscope.

Investigation: Nikos Morfonios

Data analysis and visualisation: Openpolis

9/8/2024

Credit: Εuropean Union-EP

- Greece is spending the largest part (37%) of its green-transition money on renewable-energy projects. Only 11% is going to projects that directly address climate change.

- Of the 172 green milestones and targets, the Greek government has yet to meet 79% of them.

- To date, disbursements for green investments are stalled at €3 billion, while Greece has access to a total of €14.3 billion in green bonds.

- Greece’s renewables projects are in trouble due to inadequate planning. A much-postponed study is expected in late 2025. In the meantime, the country risks being hauled before the European Court of Justice for the irregular siting of wind turbines.

- None of Greece’s projects have involved proper environmental auditing. But Greece is nonetheless betting on the untried technology of carbon capture and storage.

- The recovery plan’s “no significant harm” principle looks inadequate from an environmental standpoint.

The term “green investment” has long since lost the prestige it once enjoyed. Renewable-energy installations (wind turbines, solar photovoltaics, etc.) now encounter systematic opposition from Greek country-dwellers. Meanwhile, a pile of money from the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) has become available to fund the so-called green transition and promote Europe’s self-sufficiency in energy. So what will this transition involve? And will proper protections be afforded to the local environment?

The European Data Journalism Network (EDJNet) and the Mediterranean Institute for Investigative Reporting (MIIR) have put the European Commission’s own data under the microscope, alongside the national recovery plans of Greece and 10 other countries in southern and eastern Europe. We hope to shed light on the real impact of the projects funded by the EU scheme.

How much of Greece’s allocation is going to climate targets?

The new EU money means different things for different EU countries. For some, the recovery fund represents a unique opportunity to achieve development. This is particularly true for the countries of southern and eastern Europe, which have received the greatest funding in relation to GDP. These include Greece, Croatia, Spain, Romania, Romania, Italy, Portugal, Poland, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Hungary and Slovakia. It is why we chose to look at these countries in particular.

All 11 countries examined are meeting the requirement that 37% of their allocation be invested in the green transition. Some exceed it by far. In particular, Hungary devotes 67% of its resources to climate and environmental objectives. Bulgaria, in second place, is also spending more than half (57%) of its funds on green measures, and Slovakia and Poland are close behind with 48% and 47% respectively. Greece is in tenth place with 38%.

A more detailed breakdown of green-transition spending shows that Greece (together with 4 other countries: Poland, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Hungary) committed the largest share of its money to renewable-energy projects. Four countries (Croatia, Spain, Portugal and Slovakia) targeted energy efficiency measures. Only two countries (Romania and Italy) directed the lion’s share of their money to sustainable transport projects.

It is hard to know with certainty why countries decide to invest more in one target than another. However, we can speculate about their motivations. For example, Poland, Hungary and Lithuania have invested more than half of their allocation in renewable-energy projects. Eurostat figures show that Poland and Hungary in particular rank last among EU countries for renewable-energy consumption. They therefore have an extra incentive to invest in this area in order to comply with existing European targets.

But this is not the case of Greece’s national plan, which nonetheless directs much (37%) of its money to renewables. Based on the same Eurostat statistics, Greece is in the middle of the European pack in terms of renewables with 22.7% (representing the total renewable share for transport, electricity, heating and cooling). The EU-27 average figure is 23%.

So why did Greece choose to invest disproportionately in renewables projects compared to other areas, notably energy efficiency (33%, mainly meaning the renovation of poorly insulated buildings)? And why is it investing so little in climate mitigation and adaptation (only 11%, even though this challenge is a critical concern for Greece) or in transport (3%, despite major deficiencies in Greek cities, especially Athens)?

“The Greek recovery plan was not done properly”, argues Theodota Nantsou, head of environmental policy at WWF Greece. “Where the money should have been channelled, and it was an opportunity, was the Greek building sector. That is, upgrades for energy efficiency, and better insulation of buildings. The climate crisis is coming and it will hit the building stock mercilessly.”

No thermal insulation

Of the approximately 6.5 million residences in Greece, more than half were built before 1980 and so have no thermal insulation. Based on data from Greece’s Ministry of Environment and Energy, 77% of those homes that have been issued energy performance certificates are classified in the three worst classes (E, Z and H), while less than 5% are in the two best classes.

Greece’s national “Save” programme uses the recovery fund’s resources for the thermal renovation of houses, but it is “completely inadequate”, says Nantsou. “It is too little money when Greece has such leaky buildings. This was a huge opportunity to upgrade the building sector so that basements, and old apartment buildings, and houses in villages that depend on coal and fire-burning stoves, are viable.”

The issue of thermal insulation of buildings is critical for another reason: it is inextricably linked to energy poverty, i.e. people’s inability to pay for the electricity and fuel that will keep their homes at tolerable temperatures.

As things stand, heating and cooling can be an expensive luxury for energy-poor Greeks. According to Eurostat data, more than one in three of them (34%) do not live in an adequately cool home during the summer months.

Credit: Freepik

Renewables without proper planning of land use

There is another conundrum at the heart of Greece’s national recovery plan. Despite the large share of investment channelled to renewables projects, local environmental protection has been poor.

Most of the measures included in the Greek plan did include zero-cost commitments to improve the regulatory framework in this or that area. In terms of the green transition, such commitments were “piecemeal and basically intended to benefit renewables”, Nantsou explains. They do not deal with Greece’s longstanding issues of poor land-use planning and environmental regulation.

“Greek renewables are indeed progressing rapidly”, she notes, “but that is because there is sun and wind, and not because the permitting process is good or because of proper land-use planning which tells the investor where and if the wind installation can be built.”

Wind-farm park at Petra Skeli, Crete – Credit: Documentary “Askos tou Aiolou”

Wind farms off the leash

It is for this reason that the EU Commission has an ongoing infringement case against Greece for its uncontrolled siting of wind farms (the procedure is stuck at the consultation stage since February 2023). Greece has no proper land-use plan for renewables, as the existing one is outdated (2008) and does not comply with the EU directive on the protection of Natura sites.

In a routine annual meeting with staff of the Greek environment ministry, Commission officials recently warned that Greece is now likely to be referred to the European Court of Justice “given that the revision of the renewables land-use plan, which should include an examination of cumulative impacts, is postponed from year to year”.

The environment ministry’s most recent such postponement runs till the end of 2025. The tender process for commissioning the study was launched in 2019.

Given this problematic framework for developing renewables, the Greek government added a clause to its recovery plan that will strengthen the regulations for offshore wind farms in particular. The same provision also provides for the “review” and “optimization” of land use for other renewable-energy projects, such as solar panels on agricultural land.

It is no coincidence that in the list of the 100 largest recipients of funding from the European recovery fund, a number of wind and solar operators are prominent, such as Terna Energy, which received the 12th largest grant (€250 million). Among the projects listed on the “Greece 2.0” website, “an electricity storage system crucial for the development of renewables” was prominent, with a budget of €200 million. The list also includes controversial carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects, which will be discussed below.

It is worth noting that this list of the largest recipients was last renewed in November 2023: the Greek government has not adhered to the fund’s requirement to update the list twice a year. Based on the EU Commission’s guidelines, the recipient is considered to be the entity (a company or individual) that receives the fund’s resources directly and is not a contractor. Hence the list contains ministries and public agencies that subsequently contract out the projects, and it does not include all the private contractors that emerge after contracts are awarded. The same applies to the list of projects on the Greece 2.0 site, such as the aforementioned renewable-energy storage systems. For such projects it is nonetheless indicated that a competitive tender procedure will be followed for the contractors.

Credit: Pixabay

No reform of the environmental audit system

At the same time, Greece’s national plan includes no reform of environmental auditing. On this, Nantsou, of WWF, is unequivocal: “There is no serious environmental control in Greece. At the moment, anyone goes where they want and builds what they want, and they know that it will be legalised after a few years. They don’t pay the taxes they should, they don’t make sure they get a building permit as they should, or do the study as they should, or dump the waste water as they should. And then the real cost, the environmental cost, is borne by us all.”

Greece “has not set milestones and targets in order to build a robust control mechanism that is proven to help, as the OECD and the EU have said”, argues Nantsou. “When you have robust control mechanisms, you have a healthier environment, better innovation and healthier economic activity. Such reforms have not been included in the Greek plan.”

Far behind in meeting milestones

Regarding the fulfilment of the 172 milestones and targets and the 71 deadlines featured in Greece’s recovery plan, Greece has so far failed to meet 79% of them. This situation is also true of other countries in the region. Italy and Croatia have only met 25% of them.

€3 billion received so far by Greece for green investments

The total amount disbursed by Greece from the recovery fund for all the pillars of the programme stands at €17.2 billion, according to the Greece 2.0 website. Greece is entitled to receive €36 billion in loans (€17.73 billion) and non-repayable grants (€18.22 billion), which in total represents 16.2% of Greek GDP.

According to the data on NextGenerationEU green bonds (the financial mechanism that feeds the climate-related resources of the Recovery and Resilience Facility), Greece is eligible to receive €14.359 billion, which ranks it 5th among EU countries.

According to EU Commission figures, Greece has so far received a total of €2.84 billion under the green transition facility and an additional €153 million of initial funding under the RePowerEU programme, totalling almost €3 billion. The equivalent figure for Italy is €15.5 billion, with Poland in second place (€7 billion) and Spain third (€6.6 billion).

Carbon capture and storage: a controversial technology

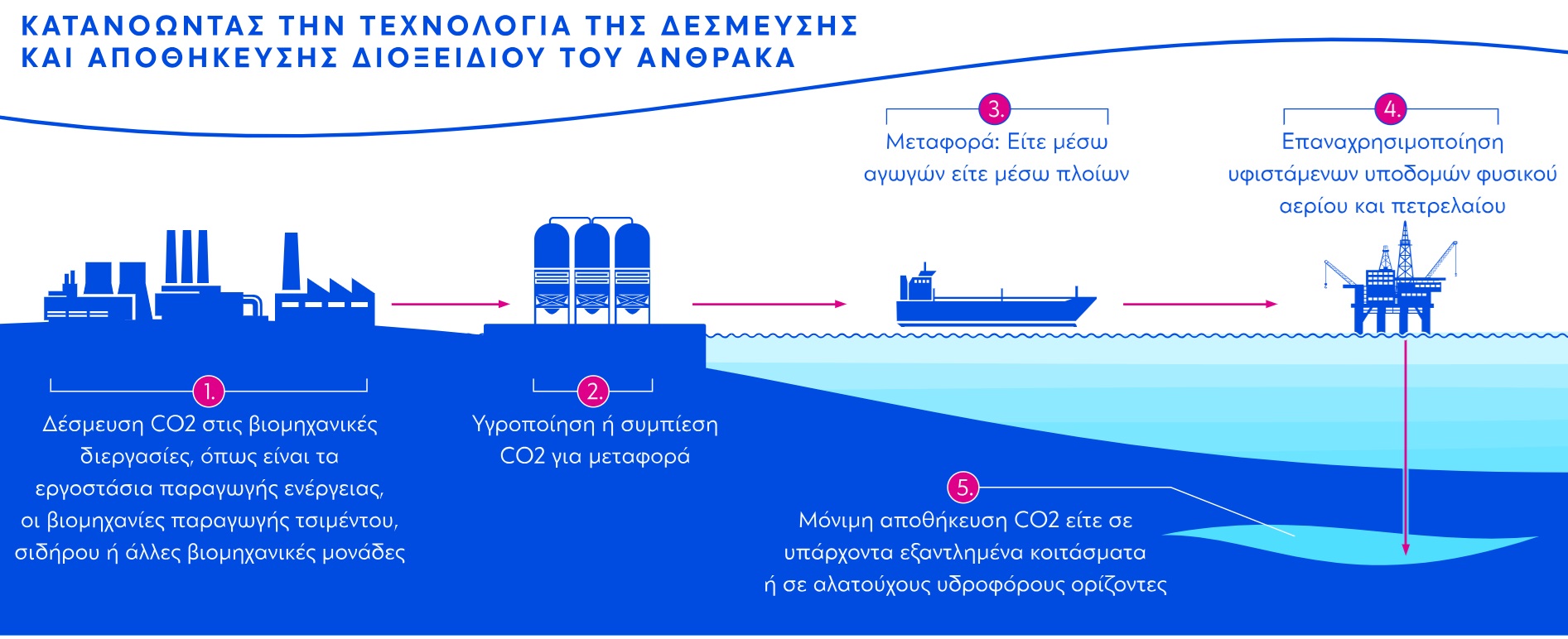

The Greek plan includes carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects. This technology allows carbon dioxide to be captured from factories and power plants, then compressed and stored in repositories in natural geological formations underground. It is controversial and possibly dangerous.

Specifically, the Greek plan provides for “the establishment of a legal framework, a licensing framework and a regulatory framework for carbon capture, usage and storage technologies”. Two specific investments were made: one to provide financial support “for the development of the first CO2 storage facility in Greece” and the second concerning “CO2 transport”.

The first and largest investment relates to a project of the company Energean, which is developing Greece’s first CO2 storage facility. This involves the conversion of “depleted” oil reservoirs in the subsea basin of Prinos near Kavala (northern Greece) into geological repositories. The project has been included in the Produc-E Green action plan, and has a total budget of €300 million. However, the final amount of its subsidy remains unconfirmed, as this particular plan includes different categories of subsidy which encompass the production of electric cars, chargers and batteries, as well as recycling.

The second investment, under RePowerEU, concerns the construction of a pipeline in the Attica region. This will connect two cement plants to a liquefaction terminal (possibly in Revithoussa), from where the liquefied CO2 emissions will be transported by ship to the storage site in Prinos.

Right from the public-consultation stage, environmental organisations have been opposed to the inclusion of CCS investments. In a comment on the matter, WWF argued that CCS “is extremely costly and offers a questionable and scientifically unproven contribution to climate change mitigation” and that its use is not a “panacea for decarbonising industry and should not be an excuse” for avoiding it.

Nantsou elaborates: “This is essentially a fairy tale of the oil industry. In most cases it is being used as a means of mitigation, to absorb the industry’s own emissions. This way they can continue their polluting activity by burying their emissions.”

CCS is risky since it involves burying the carbon dioxide in rocks under high pressure, a process that can cause dangerous leaks into the subsoil. Although the technology is experimental, this has not stopped industries from requesting exemptions from their obligation to reduce their pollution on the grounds that they will later install CCS.

Worse still, in this case the risks are not limited to those mentioned above. The document accompanying the storage permit for the Prino investment makes clear that the prospective carbon repository is only partially depleted. In its words, “care will be taken to ensure that any potential oil or gas extraction will be limited to the necessary needs to manage pressure and ensure the safety of the storage sites, and any such extraction will only take place if it is necessary for the safe storage of CO2. The CO2, together with any oil or gas that may be extracted, will be separated and returned for permanent storage.”

Credit: Hellenic Hydrocarbons and Energy Resources Management Company (HEREMA)

“No significant harm”: an inadequate principle

According to the technical guidance provided by the EU Commission to the member states, the so-called “no significant harm” principle must be applied to all projects included in national recovery plans. This stipulates that no measure should cause significant harm to existing environmental objectives.

Beyond the obviously ambiguous nature of the term (i.e., the definition of what constitutes significant harm), the Commission has been criticised from the outset by environmental groups for its failure to ensure that the recovery measures are accompanied by environmental protection.

Green10, an umbrella group of ten international environmental organisations, complained in a public statement about the principle’s simplified criteria as presented in the technical guidance. It would appear that the environmental assessments of projects undertaken by each EU country was a simple matter of box-ticking on questionnaires.

After reviewing a number of European projects, Green10 found that “the assessments carried out by member states under the ‘no significant harm’ criterion were of poor quality and would not be effective in preventing environmental harm”.

In particular, “many recovery plans do not contain enough detail to allow for an assessment of their environmental impact”, while some “approved measures do not even specify the exact locations or details, and therefore the measures should not have been approved”. For example, one approved plan included funding for 29 irrigation projects whose locations were not even disclosed! Unfortunately, such cases are not the exception, notes the environmental group. “The assessments provided by member states did not accurately reflect the potential damage of this and other such projects. That will only become apparent later in the process, when the funds have already been disbursed.”

By then it will be too late. The damage will have been done, and the money spent.

How the EU’s recovery fund works

The EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is expected to be complete by the end of 2026. The programme, introduced by the EU in 2021, has allowed member states to access resources from the so-called NextGenerationEU programme in the form of both loans and grants. The intention was to promote Europe’s economic and social recovery after the Covid pandemic.

Each country developed its own national plan, detailing its resources and its specific measures (investments or reforms), milestones, targets and deadlines. In order to receive both the grants and the loans, countries’ national plans had to meet criteria linked to the six pillars of the RRF, namely: the green transition; the digital transition; economic cohesion, productivity and competitiveness; social and regional cohesion; health, economic, social and institutional resilience; and policies to help young people.

While countries have some freedom to choose how much to invest in which sectors, there are very specific criteria that must be met to access the funds. Among these, a focus on the environment and the green transition is key. All national projects are required to allocate at least 37% of the total funding from the RRF to green-transition measures.

This choice is in line with the policies and objectives that the EU has put in place in recent years, notably the European Green Deal.

Furthermore, as an additional support for the green transition and in response to the energy crisis caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine, the EU introduced the RePowerEU programme in 2022. This provides additional resources – which countries can build into their national plans – that specifically target European energy infrastructure. The aim is to make Europe more independent of Russian energy imports.