Trapped in paradise

THE DARK FACE OF THE GREEK TOURISM INDUSTRY

Posted workers in the EU: how letterbox companies based in Bulgaria are getting away

with overworked, underdeclared and underpaid workers in Greek hotels.

A months-long cross-border investigation about the hotel industry.

By Lina Kapetaniou and Elvira Krithari, Ioanna Louloudi, Ilias Stathatos, members of MIIR.

Additional reporting in Bulgaria by Stanimir Vaglenov and in Romania by Timea Hont.

Date of publication: Saturday, March 14, 2020

Τhe journey to the dream destination turns into a nightmare

Adam turned his face away from the bright light of the sun, as he was getting off the airplane on the tarmac of Heraklion airport in Crete. It was the 25th of April and as the sun rose higher, the temperature climbed to 26°C. He was tired from the flight from Manchester to Heraklion but his face broke into a smile, once he caught a glimpse of the shimmering sea. He carried his luggage and got into a taxi to Elounda. During the 1,5 hour ride he kept dreaming of the next months. He had left behind the cloudy, dull weather of Staffordshire in the Midlands in order to pursue a summer job in a hotel in Greece.

“I went there to experience the lifestyle, I just really wanted a change in my life and not to regret that I never took the chance”,’ says Adam Judd, 32, as he remembers how he felt, crossing the gate of Porto Elounda Golf & Spa Resort, one of the most prestigious 5-star luxury resorts in Greece. He couldn’t possibly imagine what would follow the next weeks and how his dream summer job would turn into a nightmare.

Art Direction – Motion Graphics: Alexia Barakou, Sound Design: Alexis Koukias-Pantelis

Adam is one of the hundreds of foreigners that worked in Greek hotels during the summer of 2019. During a months-long investigation our team was able to uncover a complex scheme involving a recruiting agency based in Greece and letterbox companies in Bulgaria that enlist young employees or apprentices from other EU or third countries to work at top Greek hotels, by manipulating vague EU regulations on “posted workers”. Through this operation, hundreds of young people have ended up as overworked, under-declared and underpaid foreign workers in Greek holiday resorts over the past years, while hotels have avoided heavier taxes and social security contributions.

Following the economic recession and the EU-IMF imposed fiscal austerity of the past years, Greece’s tourism industry has been considered to be the country’s “lifejacket”, creating new jobs and generating growing revenues. However, the deregulation of the labour market and the need for a cheaper and more competitive workforce has also become fertile ground for anyone eager to rig the system for a larger profit margin.

Our investigation brings to light a pattern of systemic violations of labour laws in the Greek hotel industry, bringing these to the attention of Greek labor inspectors and posing fundamental questions for the future of a sector so crucial to the economy. For the needs of this report we travelled across Greece and Bulgaria, collaborated with investigative journalists in Bulgaria and Romania, examined numerous legal documents, monitored a series of online platforms and social media pages, and interviewed dozens of people who came to work in Greece over the past summers.

So how exactly has this elaborate scheme that results in wage dumping and exploitation of foreign workers, flew under the radar of Greek, Bulgarian and European authorities?

Contents

“Fishing” for employees using Greek summer as bait

For Agnieszka Plonkiewicz, 24, the job offer came through her university, WSB in Poznań, Poland. She started working at Istion Club Hotel & Spa, in Halkidiki on the 27th of June 2019. “My university sent me an email about Job Trust. I checked their website and it looked like a dream,” she explains. “The university provided me with health insurance and I signed a contract for three months. My motivation to choose Greece and this internship was to learn, gain work experience, meet new people and have a nice time in a sunny place.”

It wasn’t long before Agnieszka realised that things were not going to be as she imagined. “I had the worst three months of my life. I was standing in the kitchen for 8-9 hours a day, with a wall in front of me, next to the noisy washing machine and the hot stove, polishing cutlery. I had to fight with my manager for one day off. When I told him I had come to Greece to learn, he just laughed out loud”.

A few miles away, at the Aegean Melathron Hotel in Kallithea, Chalkidiki, Vlad from Romania (his full details at our disposal) was also excited for this opportunity he got through the Erasmus Programme at his university, Alexandru Ioan Cuza of Iași. He worked at the hotel from the end of July until the end of September. That last month he worked for 30 consecutive days, without even one day off. “I didn’t have any days off, because many of the staff had left. I was living in the basement of the hotel together with another Romanian employee.”

All the aforementioned employees came to work in Greece, after applying to Job Trust. As the company’s website mentions, “the human resources consulting company has been operating for more than 15 years with the main objective of recruiting workers in order to fill vacancies in luxury hotels and resorts in Greece and abroad”.

Doing business with universities

In all its social media, Job Trust advertises summer jobs “with a taste of holidays”. The company’s videos of long, sandy beaches, cocktail sipping by the pool, modern spacious rooms and local food that looks scrumptious have thousands of views on YouTube, while the taglines “enjoy your summer while working in Greece” and “combine your summer holidays with a tourism job” get numerous likes across social media platforms.

Job Trust has a very broad online presence in numerous job websites, search engines and online job boards, such as eurojobs, cvrain.com, avalanchejob.com, learn4good, hosco, justlanded, profdir, etc. It also participates in virtual job fairs of the European Job Days, that are run by EURES, the European Commission’s job mobility portal. Furthermore, the company lists its summer vacancies to many popular websites for internships, student jobs and Erasmus opportunities such as erasmusintern.org, studentjob.co.uk, erasmusu.com, teli.asso.fr.

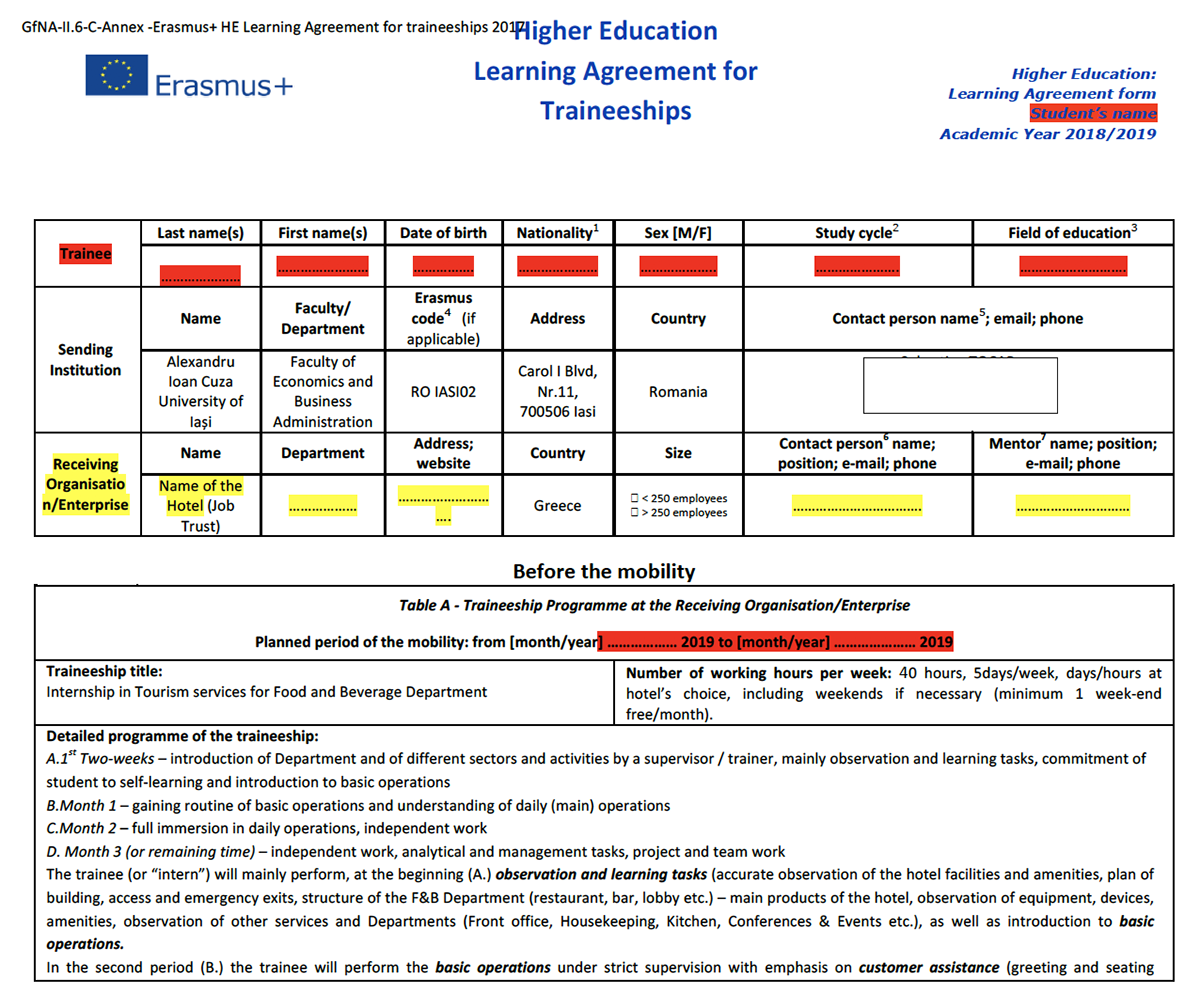

With some educational institutions, Job Trust has even tighter connections, like the WSB University in Poznań that informs students on its available job vacancies, as former employee Agnieszka Plonkiewicz described, or like Ecam Rennes Engineering School in Bruz, France, as another student recounted. Alexandru Ioan Cuza University in Iași, Romania has been collaborating with the company for the last 7 years. “We have around 60-70 students per year from our faculty going to Greece by means of the Job Trust company. They are hired as interns”, Dorina Moisa, from the International Relations Office of the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, explains in an email sent to our team. The student and the university sign official Erasmus Programme documents with Job Trust.

Official Erasmus documents regarding the cooperation between the

Alexandru Ioan Cuza univerity in Iasi Romania, with Job Trust.

As far as the university knows, the student is hired as an intern who will spend the next few months gaining significant skills and work experience.

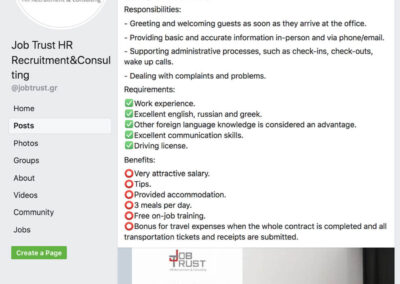

Entering the “promised land”

All prospective employees have to fill out an online application on Job Trust’s website, undergo a phone interview and receive a job offer in their email inbox . The job offer may include positions in one or more hotels, from which the applicant can choose, and informs the applicant of the future working hours and monetary compensation per working day. In the following email, which was sent to a candidate ahead of 2019’s tourist season, the working hours are stated as 8-9 per day for 5-6 days a week. The proposed daily wage is 16-22 euros per day.

Job offer received via email proposing a daily wage of 20 euro.

The candidate has the chance to choose between various hotels.

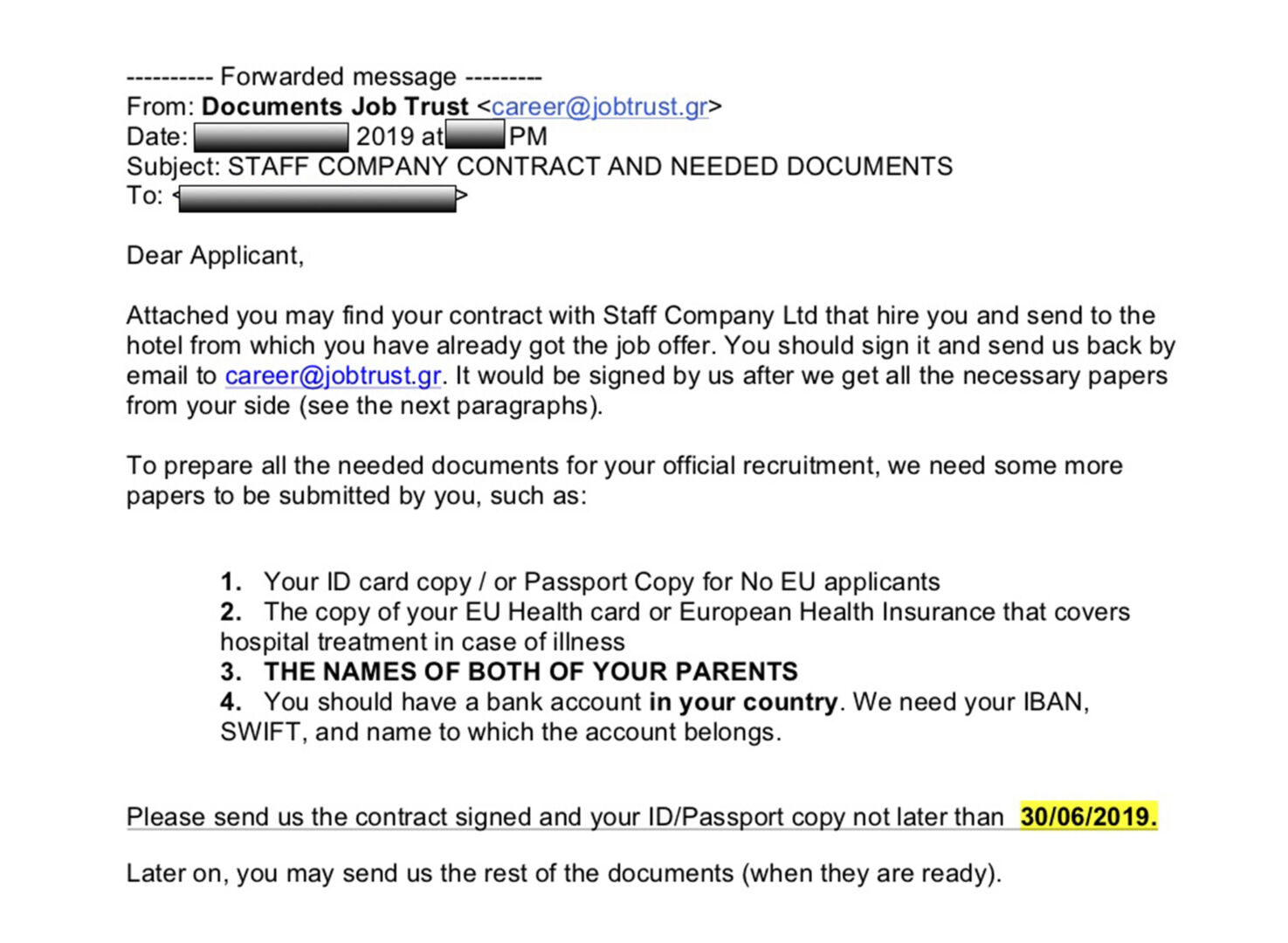

Once the applicants select a hotel to work at and accept the offer, they are, as promised by the agency, sent an email such as the following:

The email is sent to prospective employees from the [email protected] email address,

but contains a contract with STAFF Company.

The moment this email arrives in their inbox, prospective employees discover that they will not be employed by the hotel itself, nor by Job Trust. Instead, they will be employed by a company whose existence they previously ignored. The subject title clearly states that the “contract” sent to candidates is with a company named “STAFF”, however no further details are provided in the emails.

And this is where things start getting complicated.

Job Trust, with which the candidates have been in touch all along, was founded in 2006 by Irina Aslanov, a Romanian national who claims in her online cv to have been raised in Ukraine, Moldova and Russia, and later to have studied in Romania and Greece. The company – whose office is located in a residential apartment building in the neighborhood of Kalamaria, Thessaloniki that in no way suggests a busy international recruiting agency, is registered in the Greek General Commercial Registry as a private recruiting agency. It therefore is only allowed to act as an intermediary between job applicants and prospective employers who use the agency to source employees matching their criteria. This means that Job Trust cannot act as an employer, but only as an intermediary between candidates and employers.

Job Trust’s offices at the suburb of Kalamaria in Thessaloniki.

A closer look into “STAFF Company” reveals that the firm is not based in Greece, but in Bulgaria. In fact, according to the Bulgarian Commercial Register, STAFF has a registered address in the northern town of Pleven, as well as another correspondence address for taxation purposes in the same town, at the office of an accounting firm. The company was founded in February 2017 by a Greek man, Alexandros Savvidis. A search into the owner of STAFF company in Greece was unable to deliver any clues about his professional background. It did reveal, however, a very crucial detail: Alexandros Savvidis appears to be a partner to Irina Aslanov, the founder and manager of Job Trust.

We sought more answers about this “mystery” company in Bulgaria. A search in the Commercial Register came back with important information, such as documents dating back to the company’s establishment, where this Greek entrepreneur claimed his personal address to be the village of Neo Risio near Thessaloniki and a PO Box. However, instead of providing an actual PO Box number, Savvidis appears to provide a municipal registry number, essentially providing the Bulgarian authorities with false information about his actual residence. Furthermore, from the register it becomes clear that Savvidis has founded or managed a total of eight companies since 2010, all of which are still operating. And as we were soon to find out, foreign students and jobseekers that were recruited by Job Trust to work in Greek hotels had been signing work agreements with the companies of this particular unknown Greek businessman for the past nine years.

The web of Bulgarian companies and the empty offices

Driving up Ruse Boulevard in the town of Pleven, in northeastern Bulgaria, we arrived at a tall, rusty soviet-style apartment bloc. It takes a while to track down the exact location for STAFF Company’s registered address. At number 87, building B, the dark and damp corridors lead up to apartment 6, where there is no sign whatsoever of a staffing firm. A plate on the black wooden door warns that the flat is guarded by dogs – a fact that a ring at the bell quickly confirms. However no one arrives to open the door, and the company’s letterbox seems empty as well. It is quickly made clear that if the company had an actual operating office, it wasn’t there.

According to the Bulgarian Commercial Register, this is the building housing the offices of STAFF Company in the town of Pleven.

The same becomes evident as we visit the registered addresses of the other companies that Savvidis has established in locations all over Bulgaria: Plovdiv, Veliko Tarnovo, Pleven, and even the remote village of Malka Cherkovna in northeastern Bulgaria, where STAFF Company was first set up in 2017, at a time when, according to that year’s Bulgarian census, the village was inhabited by only 13 people. Apart from an old plastic board for “Job Trust” that is left hanging on the wall overhead a travel agency in the town of Plovdiv, promoting the website of the Greek recruiting agency and some non-operative company telephone numbers, in Bulgaria we came across nothing but letterboxes and non-existent offices.

A sign advertising Job Trust in the town of Plovdiv.

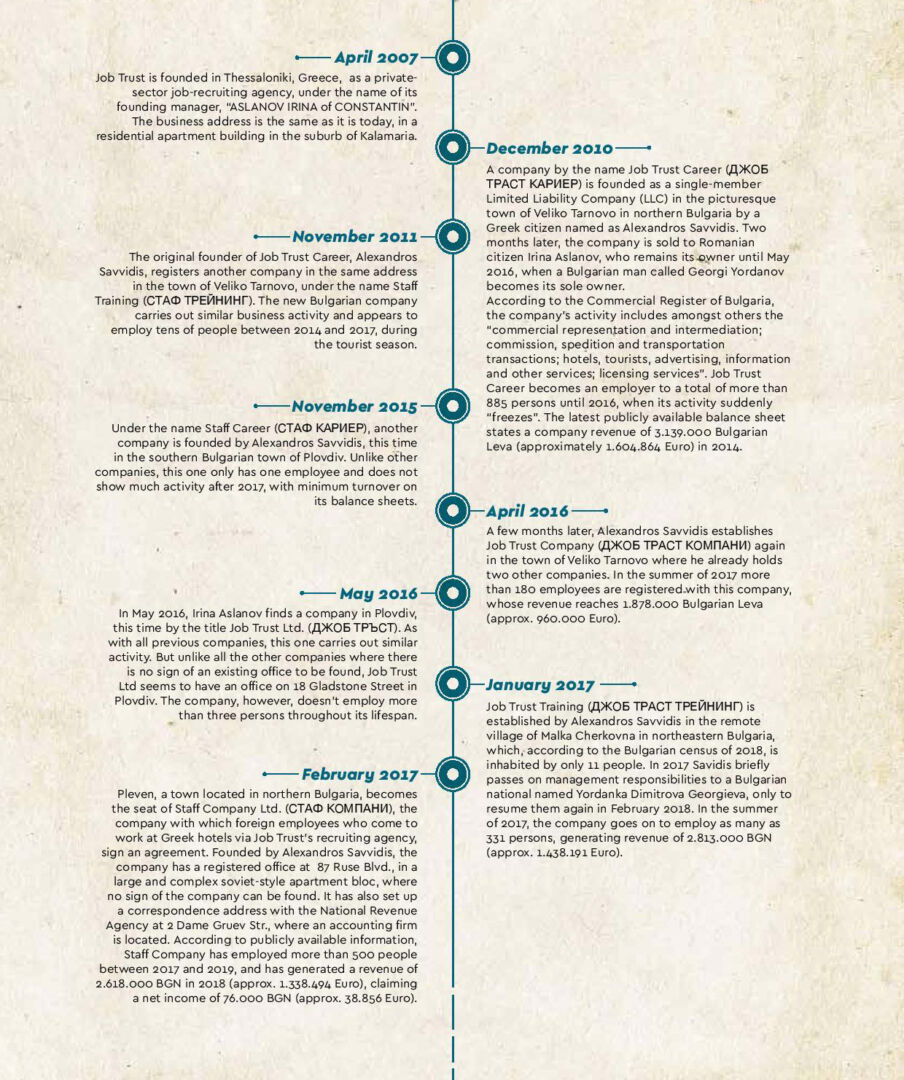

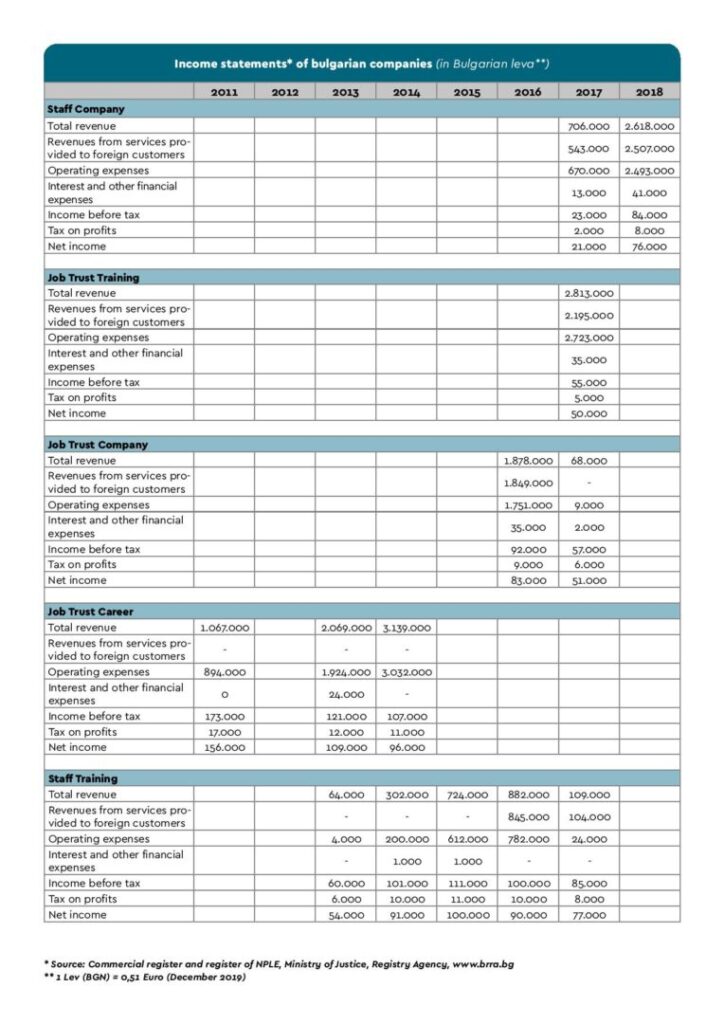

Savvidis’ companies, which carry similar sounding names with Job Trust and STAFF –Job Trust Career, Job Trust Training, Job Trust Company, Job Trust Ltd., Staff Career, Staff Training – were one after the other registered over a course of seven years, usually demonstrating peak activity during one particular tourist season and then slowly bowing out, each giving way to the next company.

Job Trust’s trails in Bulgaria

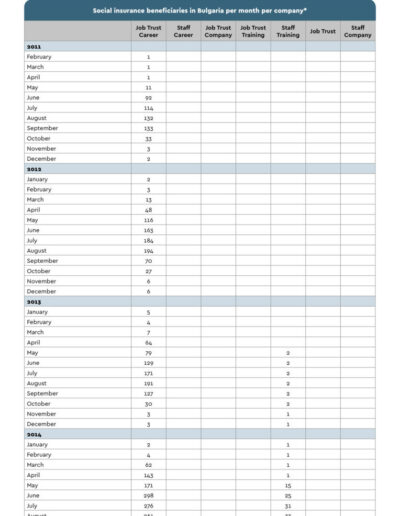

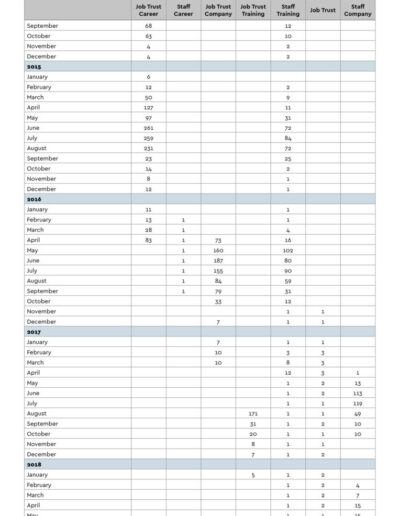

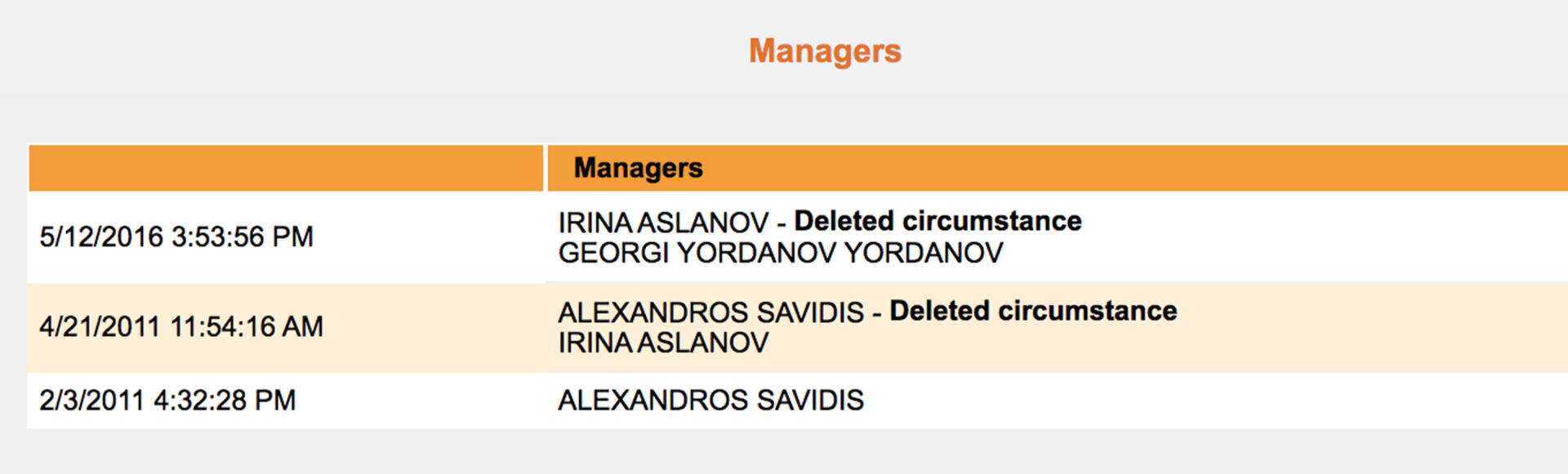

As public records of social insurance contributions show, over the course of ten years, Savvidis’ Bulgarian-based companies went on to hire more than two thousand employees.

According to the Bulgarian Commercial Register, STAFF company’s activity to this day includes “commercial representation and intermediation; brokering transactions, transportation agreements, hotel, tourist and advertising services; information services and other services”. It is this activity that was likewise undertaken by all of the previously established companies.

The tables above show the official number of registered employees

insured in the companies between 2011-2018.

In fact, the only indication that any of these enterprises might actually still be operating, were the offices of “Omega”, the accounting firm that stands as a point of official contact with STAFF Company and Job Trust Training. According to the Bulgarian commercial register “Omega” belongs to a Bulgarian national named Yordanka Dimitrova Georgieva, who for a short period of time in 2017, had also assumed management responsibilities for Job Trust Training. During her time at the helm, that company went on to sign on as many as 331 employees (July 2017).

“Company cemeteries”

In contrast with Greece, Alexandros Savvidis appears to have taken a more active role in Bulgaria, even participating himself in 2015 at a presentation for the students from the “Dimitar A. Tsenov” University of Sofia, to discuss “the opportunities for work in the best hotels and student internships in the field of the servicing sector in Greece”. In a press release about the event on the private university’s webpage, Savvidis is credited as the “owner” of Greek-based Job Trust, which, according to the same article, at that time collaborated “with about 130 universities specializing in tourism training from more than 15 countries such as: Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland, Austria, United Kingdom, Serbia, Moldova, Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan and others”.

As in other countries, Job Trust also recruited future employees from Bulgarian academic institutions, such as the Agricultural University in Plovdiv which has for over ten years collaborated with the Greek agency in sending students abroad for apprenticeships in the tourism sector, or the “European Higher School of Economics and Management” where in 2014 Job Trust held a series of presentations across its various departments in Bulgaria.

The picturesque alpine town of Veliko Tarnovo in northern Bulgaria.

The Greek businessman’s first actual entrepreneurial endeavor in Bulgaria was the establishment of “Job Trust Career”, which he set up in the picturesque, alpine northern town of Veliko Tarnovo that attracts many tourists throughout the year. It was in this town, often referred to as the “City of the Tsars” because of its rich history and unique architecture, that Savvidis appeared for the first time in 2010 with his partner Irina Aslanov to seek information on how to establish a company in the country.

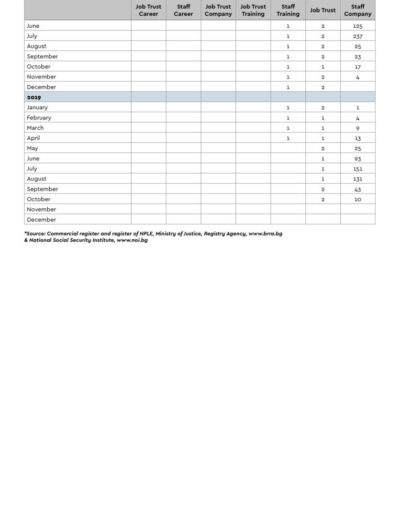

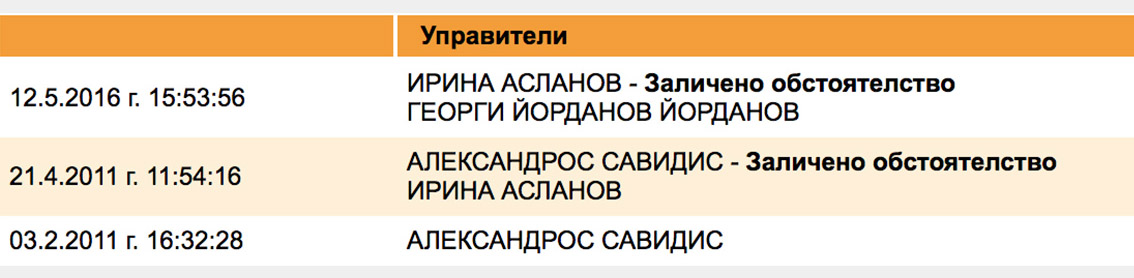

Two months after he founded “Job Trust Career” Savvidis passed the company on to Aslanov, who remained the main owner of the firm until 2016, employing more than a thousand people during the tourist seasons over those five years. Then in May 2016 the company ownership was suddenly transferred to an unknown resident of Veliko Tarnovo named Georgi Yordanov Yordanov.

According to the Bulgarian commercial register, Job Trust Career’s ownership was suddenly transferred

in 2016 to Bulgarian citizen Georgi Yordanov Yordanov.

The practice of provisionally or entirely trading in a company is not unfamiliar to Bulgarian investigative journalist Stanimir Vaglenov who has covered cases of fraud and “shell companies” in the past in his country. He calls the tactic “a cemetery for companies” and claims it it can be a strategic move that aids owners to, provisionally or entirely, avoid trouble with the law.

Businessmen at first “pretend” to sell their company to someone else, who becomes responsible for all past and new debts, and then “freeze” its activity, “burying” it under a newly founded company that resumes the previous activity under a new façade. “Most of the time the new owners were people who had no property, very often they came from minorities and were illiterate. But they would sign any document they received for very small amounts of money, maybe 50 euros, sometimes only for a bottle of brandy”, states the Bulgarian investigative journalist. “They would become owners, but they had nothing, so the state got nothing in the end. At the same time, the previous owners could freely start another company. This has been a big problem for Bulgaria that causes the state to lose a lot of money, and people to lose money from their salaries and insurance”.

The tactic has been rooted in the country’s policies that at least until 2018, allowed the easy creation of companies with minimum capital and seductively low tax rates, making Bulgaria an ideal destination for anyone wishing to avoid heavy taxation.

Investigations in Bulgaria after formal complaints

We reached out to the Bulgarian authorities to find answers. Both the National Revenue Agency (NRA) and the General Labour Inspectorate confirmed that there are currently ongoing investigations in the activities of one or more of Alexandros Savvidis’ companies.

The General Labour Inspectorate explained that a total of nine inspections have been conducted since 2016, some scheduled and some at the “request of the Hellenic Republic, through the Internal Market Information exchange system of the European Commission (IMI). Another was conducted upon request from citizens, by order of the National Social Security Institute in relation to work accidents, and one upon request from the Bulgarian Employment Agency”. The Inspectorate also relayed that on two occasions the inspectors were unable to do their work “because of a failure to contact the employer”.

According to the General Labour Inspectorate “a number of violations were found regarding the regulations on intermediation activities”. For these ascertained violations, six acts were issued, from which five penal decrees ensued. Some of these, continues the General Labour Inspectorate, “are related to not submitting employment contracts to the National Revenue Agency within seven days from their expiration. The others are associated with the migration and the mobility of the workforce”.

The latest act was served in October 2019 to one of the companies and was “related to failure to provide data on persons signing employment contracts, making it hard to determine where they come from – a Member State or a third country.” In two occasions, we were told, there was recourse to public prosecutors, because of suspicion of criminal activity associated with the handling of official documents.

The Inspectorate’s answers were also verified by publicly available court decisions. In some cases the Bulgarian courts forced the company’s owners to pay administrative fines for “violations of the conditions and processes surrounding posting and the assignment of employees in the context of services supply”.

In Veliko Tarnovo we met with the Regional Prosecutors, who informed us that an investigation had begun in 2017 as a result of a signal from the General Labour Inspectorate in Sofia concerning Job Trust Career and Job Trust Company.

READ MORE

Η The entrance to the court house in the town of Veliko Tarnovo, where we met with prosecutors

Η The entrance to the court house in the town of Veliko Tarnovo, where we met with prosecutors

working on investigations into A. Savvidis’ companies.

A man named I. Kotev who had suffered an accident while working in Greece in the fall of 2016 (he was employed by both companies in different periods), had gone to the labour inspectorate to request compensation for his accident. Τhe inspectors “began to look into the case and realized that he had no actual contract with these two companies”, the prosecutors told us. “In his testimony Mr. Kotev said that he saw an advertisement on the Internet about a position offered by JobTrust.gr and applied online. After he succeeded, they sent him by email a document called ‘conditions for work’, which mentioned the name of the hotel he was going to work at. But this was not a real contract, just a document stating ‘conditions for work’. So Mr. Kotev thought that he was signing a contract for work, when in fact he wasn’t”.

The Bulgarian inspectors noticed more irregularities when they asked for data from the National Revenue Agency and from the accounting firm that represented Job Trust Career and Job Trust Company. Eventually they realised that there were no actual hard copies of contracts submitted with the NRA, while the accounting firm only had unsigned, electronic copies of contracts, which were thus rendered legally void. “The check concluded that there are absolutely no documents that could resemble contracts. Any official documents connected to this case don’t exist on the territory of Bulgaria”, the prosecutors stressed.

What also caught the eye of the prosecutors was the fact that Job Trust Career at that time seemed to be paying Mr. Kotev a monthly salary of 500 euros for his work in Greece, but not paying the obligatory social insurance contribution, which was instead calculated on the basis of a wage of 360 Leva (180 euros). The prosecutors notified the relevant authorities about this discrepancy.

When asked about the fact that Job Trust Career had suddenly been sold to a new, unknown owner in 2016, the Regional Prosecutors replied that the event had made it more difficult to determine who is guilty, and disclosed that they had in fact questioned the last owner, Georgi Yordanov. His response to prosecutors about his involvement couldn’t have been more telling: “He said he knows only that he is indeed the owner of many companies, but he knows nothing about these companies!”. While in Veliko Tarnovo we tried to reach Mr. Yordanov for a comment, but there was no sign of him or the company at its registered address for correspondence either.

Lost in translation

Leaving Bulgaria it was clear that there was something deeply problematic in the way this web of companies has been operating. But although the companies have been under the microscope by Bulgarian authorities, hotels in Greece continued to collaborate with them in 2019. Meanwhile the Greek recruiting agency has already begun advertising online for the 2020 tourist season.

Many foreigners who had been recruited by Job Trust to work in Greek hotels in 2019, but also over the past nine years, corroborated to us that they had signed a document with one of Savvidis and Aslanov’s Bulgaria-based companies. And all of them have confirmed that the only document they were asked to sign was this particular “terms of working agreement”, that I. Kotev had also signed in 2016. There was never another contract, and they also never received a signed copy from the company.

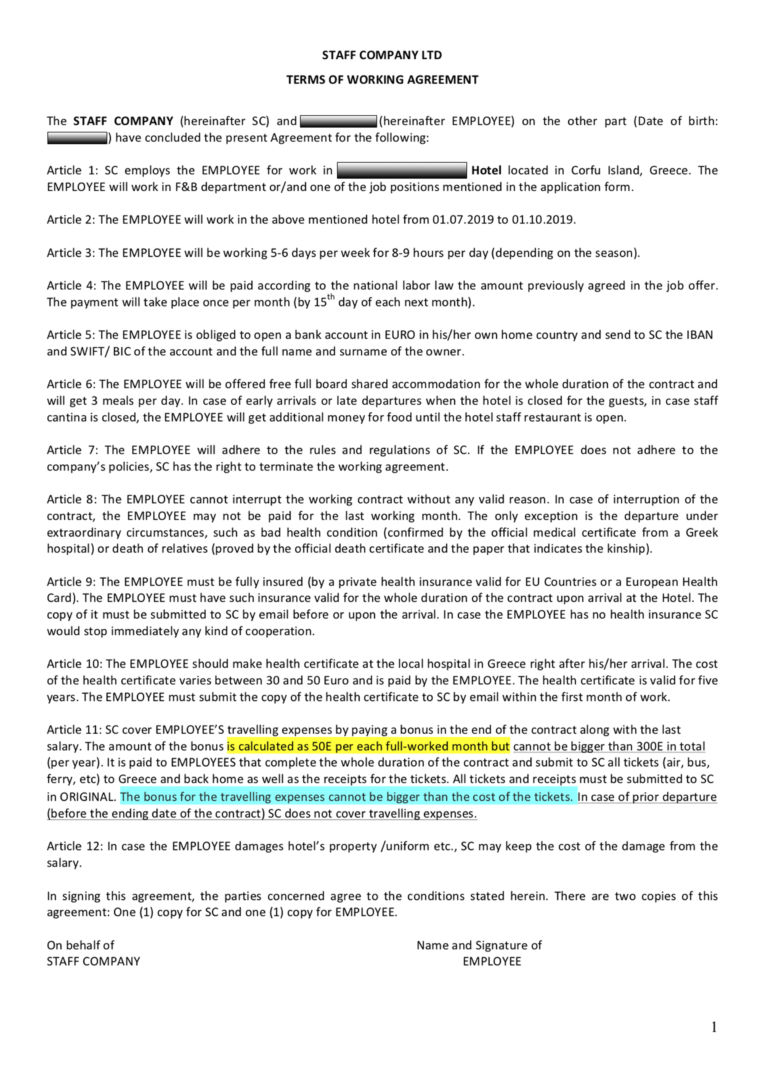

Above, the «contract» sent to employees, which states that the employee will be paid according to national legislation. It also states that if the contract is terminated, then the employee will not receive payment for the last month and that it is the employee’s responsibility to be fully insured (either by private insurance or by possessing a european insurance card).

Last summer, Teodora, a 21 year-old Romanian university student, came to work, via Job Trust, at the Aegean Creta Star Hotel in Crete in June, but quit just eight days later. “It was simply not worth the effort for the ‘salary’ you get. First of all, it was really exhausting. Every night I was finishing at 10-10.30 pm and others had to work until midnight. Most of the nights I couldn’t even get the minimum seven hours of sleep, since the next day I had to start early again. I have never worked in such a stressful and unhealthy environment”, she concludes and adds that “the strange thing about Job Trust is that they have their own set of rules and regulations. They pay you per day, not per hour worked”.

Foreign employees like Teodora who came to work in Greece in similar conditions via Job Trust, confirmed that they had signed a “terms of working agreement” with one of the Bulgarian companies run by Savvidis-Aslanov, and that they never signed any other contract, nor did they receive a signed company from the company.

None of the “terms of working agreement” documents of former employees that we managed to obtain included a precise definition of the working days and hours. On the contrary, they all mentioned -just as the initial offer they had received via email- that employees would be working “5-6 days per week for 8-9 hours per day (depending on the season)”. The documents also failed to state what the exact daily or monthly salary would be, but included the ambiguous phrase “The employee will be paid according to the national labour law the amount previously agreed in the job offer.”

Underpaid and overworked

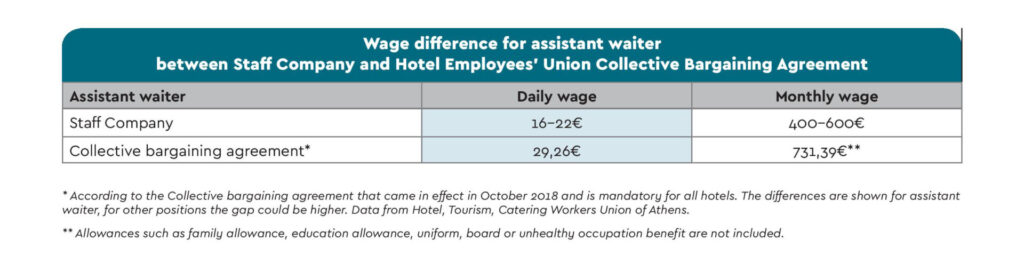

The daily wage in all job offers presented to foreign employees who we interviewed, was limited to 16-22 euros/day (depending on their experience). A small calculation shows that the monthly total salary, for a five-day working week, would range between 368-500 euros.

For example, Vlad, a 22 year-old student from Iasi, Romania spent nine weeks working at the Aegean Melathron hotel in Chalkidiki in the summer of 2019. For his work he was paid 16 euros/day, and in his bank account he received a total amount of 384 euros for 24 working days in August, and 480 euros for 30 working days in September (plus 84 euros as a partial reimbursement for his tickets to Greece.)

The Bulgarian law stipulates a minimum monthly wage of 610 Lev (311 euros approx., effective since 1/1/2020, in the years 2018-2019 the minimum wage was 510 Lev, 261 euro) for a normal working week (8 hours, 5 days). In Greece the national minimum wage is 480 euros, while for hotel employees the minimum salary sums up to approximately 730 euros, depending on the job position. So, to which “national labour law” is STAFF Company referring to in the agreements?

READ MORE

Belarusian Anton Kolbasko came to work at Capo di Corfu hotel on the popular Ionian Sea island, after applying through Job trust in June. The 20 year-old who lives in Poland, worked as a waiter for nine hours per day, six days a week. ”We had to stay overtime to close the shift, the hotel didn’t have enough workers to give people more days off,” he explains. For his work he was also paid 16 Euro per day, and claims that the working conditions were harsh and his duties way above his paycheck. “From the business perspective it’s cutting costs, but from a worker’s, it’s slavery”, Anton states and explains he quit his post early because he “couldn’t stand such an attitude from management for such a low salary”.

“From what I’ve heard, the actual salary was supposed to be higher, but probably Job Trust takes a cut from it and they only pay the amount stated on the agreement. I don’t know what the real salary is. I only know that the local people who were hired directly by the hotel are paid more than the people who work with Job Trust”, says a 21-year old employee from Romania, who over the last two summers worked in hotels in Halkidiki and Crete.

The all-inclusive bargain and the hotels

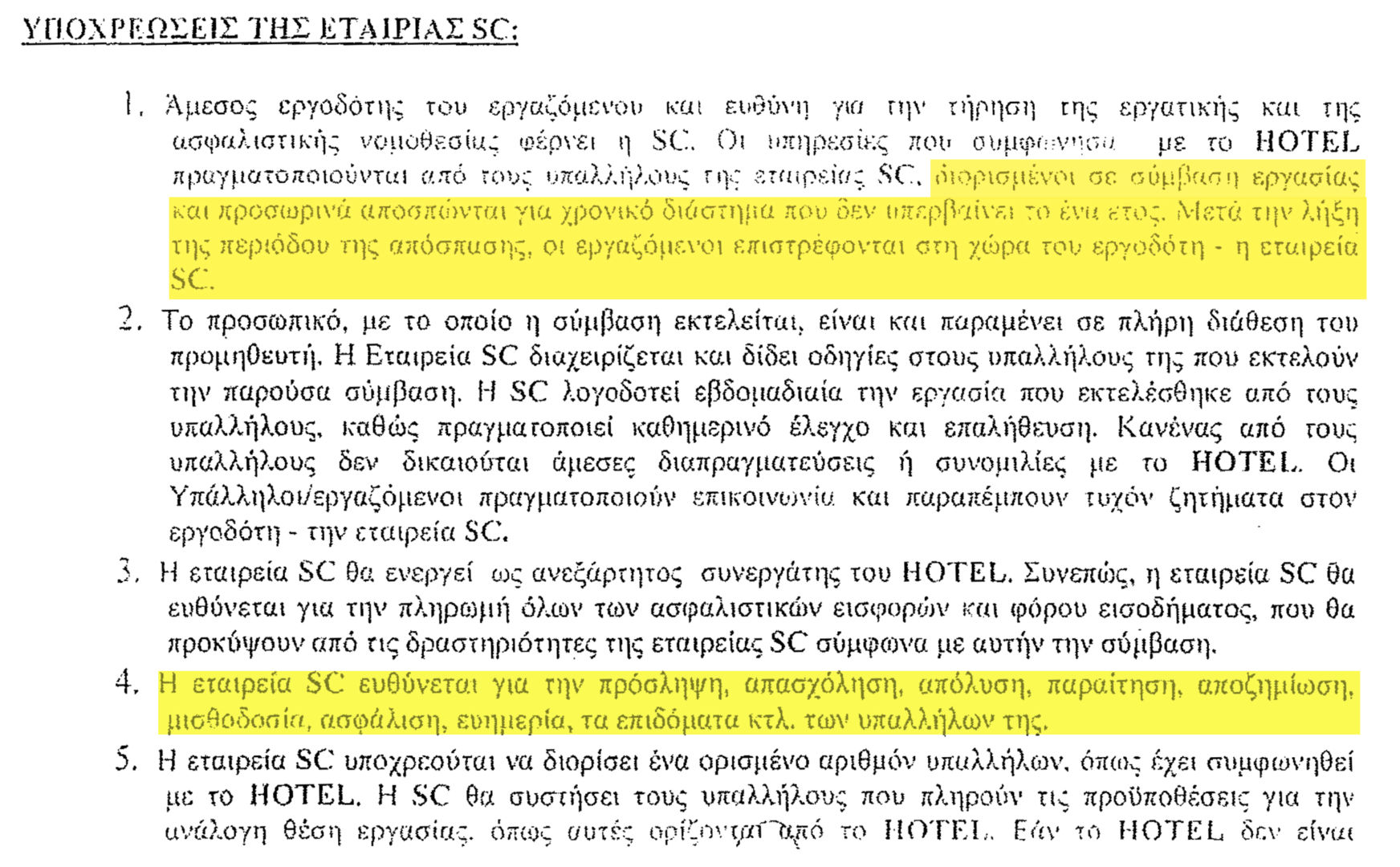

On the other hand, the owners of STAFF Company and Job Trust sign very specific contracts with the hotels that they supply with employees.

“Since 2010 there has been this company we work with, Job Trust. This year our contract doesn’t state Job Trust, but STAFF Company. But it’s the same representative, Mr. Savvidis, we coordinate with him about everything. And Ms. Aslanov, I think they are a couple,” says the accountant for a major hotel resort who spoke to us on condition of anonymity, shedding light on the inner workings of this operation.

“This year the contract states that the cost for the hotel for each employee is 33 euros per day. So if an employee works 26 days a month, we will pay 26×33 euros”, explains the accountant. “It really is a bargain. The cost is all-inclusive, we don’t pay for their insurance nor any added compensation or benefits. Any other employee would cost the hotel maybe 60 euros. This way we get two instead of one”.

In the private agreement that STAFF Company signs with hotels, an example of which is shown above, it is stated that STAFF Company “posts” the employees to Greek hotels for a period of time that doesn’t exceed one year. It is also mentioned that posted workers “communicate and report matters to the sending company”, which is responsible for the “recruitment, employment, dismissal, compensation, payroll, insurance, benefits and well-being of the workers.” The hotels on the other hand are obliged to ensure that “the board and lodging are proper and that the employees work for 8 hours a day, 5 days a week”.

Hotels that choose to partner with STAFF Company under this type of deal successfully avoid paying labour costs, higher salaries, social insurance contributions, as well as covering any liability associated with employees.

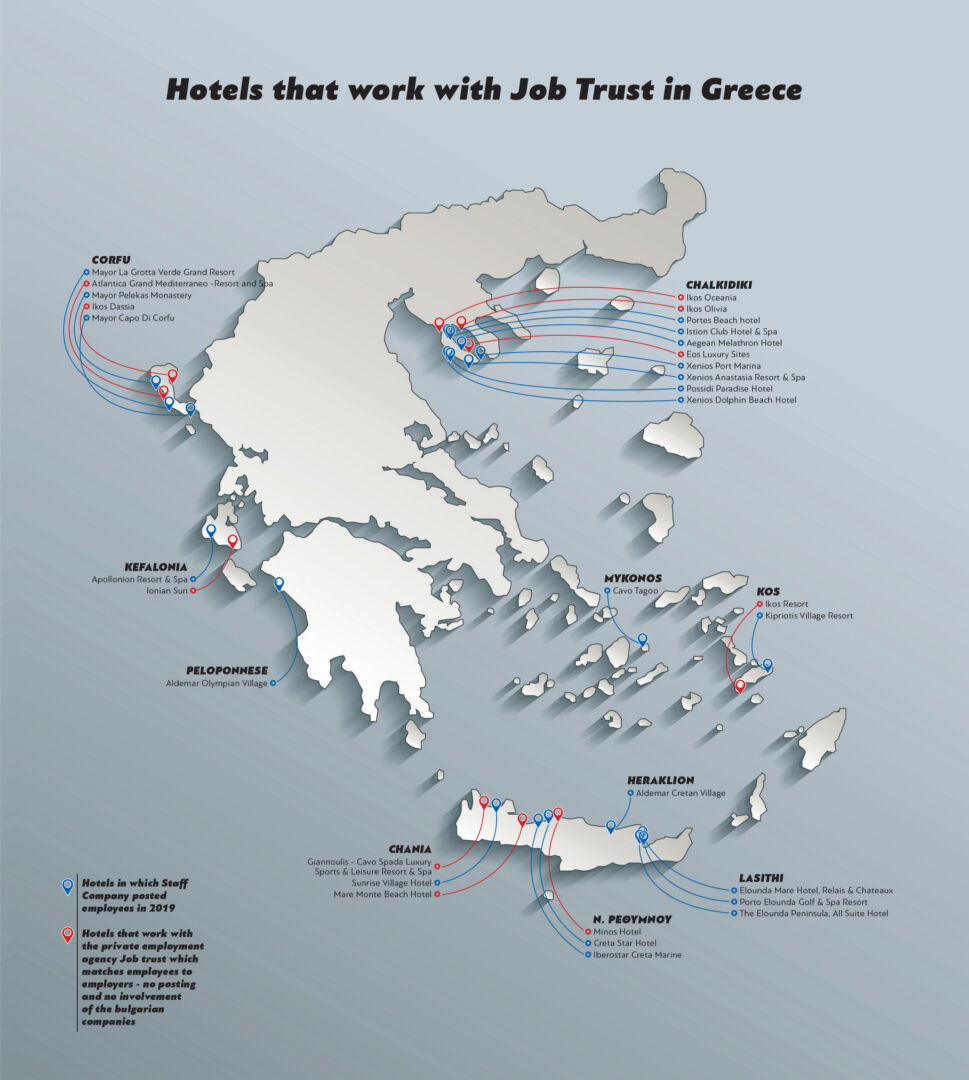

Based on interviews and on the field research we were able to establish that STAFF Company posted workers to a minimum of 21 hotel resorts in top Greek holiday destinations during the summer of 2019. Among these hotels are 5-star resorts, renowned hotel chains and acclaimed luxury hotels, all of which attract hundreds of thousands of guests from all over the world. These 21 hotels paid STAFF Company within the range of approximately 33-50 euros per day for each employee provided, while the employee was paid circa 16-22 euros per day, well below the daily wage foreseen in the existing sectoral collective agreement for hotel employees in Greece that came in effect in October 2018.

There are also other hotels that collaborate with Job Trust in a legitimate way, by directly hiring the workers the recruitment agency recommends or offering Erasmus internships to international students.

Working conditions and missing employers

Job Trust’s owner, Irina Aslanov, in a recent interview at Goabroad.com, an online platform for work and travel opportunities, reassures applicants: “We do whatever we promise to do. There are no tricks in our advertisement campaign. Before hiring, the applicant is informed about every single detail about his or her future job. We have 24-hour support for the whole duration of the working contract and resolve any kind of problems with the employers which might occur”.

Nevertheless, according to dozens of posted workers who tried to contact their employer over the course of the summer of 2019, representatives were nowhere to be found. “I tried to contact the agency, I sent them about 10 emails asking when I could leave the hotel without consequences, as I didn’t want to lose money. I got no answer”, recalls Agnieszka Plonkiewicz, referring to the term on the working agreement that “in case of interruption of the contract, the employee may not be paid for the last working month.”

READ MORE

A posted worker at the Kipriotis Village Resort in Kos island that wishes to remain anonymous, says: “The experience was very bad, the working environment was the worst I’ve ever seen, I was shocked from the first until the last day. I had so many problems from the beginning and Job Trust was not so helpful. I felt that the company could not help me. When I got all my money, I thought to hell with Greece and Job Trust”.

When employees directed their enquiries and complaints to hotel management, they were referred to the agency that arranged their posting and sent them their contract.

“I don’t think Job Trust cares at all about the employees. I had one day off every 20 days, accommodation was in the basement, it was worse than a jail, even the food wasn’t well cooked. People from Job trust told me three times that they were going to visit the hotel, but they never did,” recalls Daniela Polo Bossa, 22, from Spain that worked in Istion Club Hotel & Spa in Halkidiki.

The accountant, who works for a hotel that for years has been in business with Job Trust, provides a damning reassertion: “The hotel has been getting posted workers from Alexandros Savvidis and Irina Aslanov for the past 7 years. I’ve never met them face to face, nor anyone else from their companies. We communicated only through phone and email”.

The distortions of the posting mechanism

Art Direction – Motion Graphics: Alexia Barakou

The employees of the Bulgarian STAFF company, recruited by Greek Job Trust, come to work in Greek hotels on the basis of the free movement of workers, which is a legally protected right across the member states of the European Union.

It wasn’t long ago that the E.U. celebrated the 50th anniversary since the establishment of the free movement of workers. It was in this context that the EU introduced the term “posting” to describe the ability of an employer to send an employee to carry out a service in another country for a short period of time, in the context of an intra-group transfer, a contract of services won in another country, or a hiring out through an agency. This procedure was set out for the first time in 1996 with the EU’s “Posting of Workers Directive.” The European directive was incorporated in Greek legislation in 2000 by the “Presidential Decree 219” and was further reviewed under the “Presidential Decree 101” of 2016, because of a new related Enforcement Directive in 2014.

Greek legislative documents are quite straightforward as to the wages and allowances of posted workers: “The sending companies that post workers in Greece are obliged to guarantee to the workers the implementation of the terms of employment stipulated by Greek labour law, the national collective agreement and any sectoral collective agreement that is mandatory” (P.D. 219/2000).

It is also specified that workers, apart from basic salary, are entitled to individual allowances, including overtime pay. The salary cannot include benefits that are given to the workers for travel expenses, accommodation or food. Both the sending and the hosting company are responsible for abiding to the regulations.

But do the employees of STAFF Company actually qualify as posted workers? Does this complex modus operandi constitute genuine posting, in compliance with European and national laws?

“Several parameters need to be considered in order to determine whether this practice constitutes posting,” explains lawyer Apostolis Kapsalis, a labour relations researcher at the Labour Institute of the General Confederation of Greek workers and former Special Secretary in the Labour Inspectorate. “In particular,” he continues, “the authorities should assess, among others, elements such as the place where the sending company has its registered office and administration, where it uses office space, where it performs its substantial business activity and where it employs administrative staff. Also, to assess where posted workers are recruited and from which they are posted, the place where the posted worker usually works, if there is a working relationship between the sending company and the worker at the time of posting, and, finally, if the posted worker returns to or is expected to resume working in the Member State from which he or she is posted after completion of the work for which he or she was posted.”

STAFF Company’s employees are recruited from EU, Balkan and other third countries. They travel to Greece and begin to work for the company on the same day that their posting starts. After completing their “contract”, they return back to their home countries and their contract is terminated.

“We have strict rules about what constitutes posting. When you post someone, this person should already be working here in Bulgaria. Then a company sends this person for a short or longer period to another place to work. Before going abroad, he or she should have been working here. What this firm does is not real posting in my opinion. Maybe the State doesn’t want to regulate this problem for now, but in the future they will have to do something about it,” explains Plamena Gadzhonova, a Bulgarian lawyer, who has handled similar cases, like that of a fraudulent Bulgarian firm that manipulated posting regulations by paying low wages to employees it hired and sent to work in dire conditions as caretakers in Belgium.

Indeed, according to EU rules governing posting, a person should be affiliated to the social security system of the posting state (which for the STAFF employees is Bulgaria) for at least one month prior to their departure, a condition that is not met for the dozens of employees that worked in Greece in the summer of 2019.

As ruled by the European Court of Justice in a recent case involving Bulgaria (Case C-451/17 ‘Walltopia’), this condition can be satisfied even if the person was not in employment but was resident in that Member State. Neither of these two, employment or residence in Bulgaria, was the case for the vast majority of STAFF employees we talked to in the summer of 2019.

Letterbox companies and the European Union

It has been observed that, more often than not, abuses on posting are related to the operation of letterbox companies. There is a plethora of criteria set on a European level to distinguish letterbox from real companies, such as the existence of real facilities and offices or whether the company employs permanent staff, both in the posting and the receiving state. The purpose of establishing a letterbox company is to surpass legal and other responsibilities, such as taxation, social security contributions and generally the responsibility of employers towards their employees. According to a definition given by the EU, “letterbox companies are companies which have been set up with the purpose of benefiting from legislative loopholes while not themselves providing any service to clients, but rather providing a front for services provided by their owners. Such companies are normally very small and often only operate a letterbox, hence the name”.

Letterbox companies, indeed, often have only one post office in the country they declare as their registered office and to which legislation they are subjected to. However, their substantive business activity takes place in another state or states and thus they manage to reduce their costs, increasing their profitability.

“An unconditional understanding of the freedom of establishment under EU law, where priority is always given to economic freedoms over social ad workers’ rights, creates incentives for letter-box companies”, Per Hilmersson, deputy General Secretary of European Trade Union Confederation, told us. “Artificial arrangements without a substantial link between the jurisdiction of the company and its economic activities enables regime shopping for lower taxes, wages, labour standards and social contributions. Similarly, the rules on posting of workers can be abused by letter-box companies”, he concluded.

The European reality of inequalities

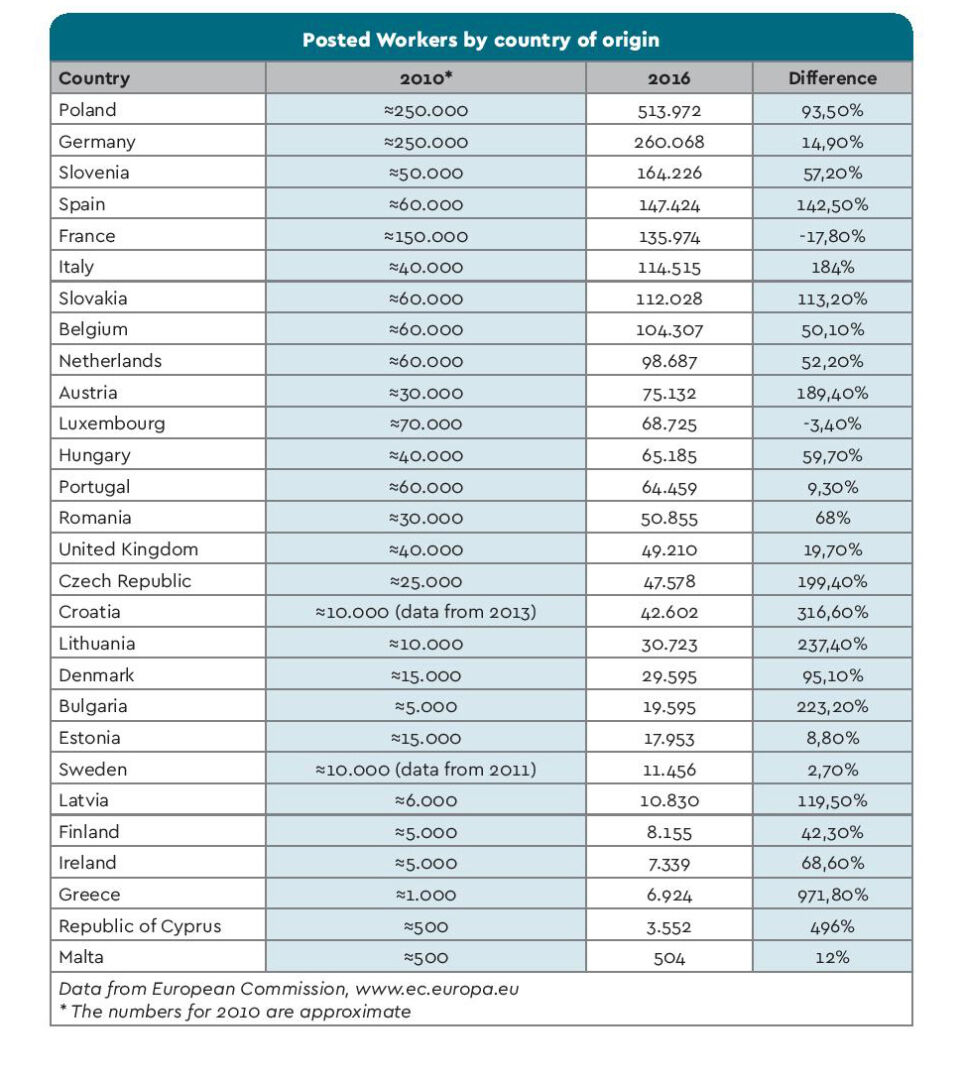

The use of posted workers by companies and businesses across Europe is rapidly increasing. Between 2010 and 2016 the number of posted workers in the EU increased by 96%. According to the most recent data, approximately 2.8 million posting procedures were registered in 2017.

The fundamental cause of problems regarding posting, however, is related to the existence of economic and development inequalities in the countries of the European Union. Although EU rules governing posting were introduced as early as 1996 in order to set the minimum conditions so that both businesses and workers could take full advantage of the internal market opportunities, the posting of workers has become fertile ground for labour abuses aimed at reducing labour costs and increasing company profits. Europe in the meantime seems stuck in trying to develop adequate mechanisms to monitor law enforcement regarding posting.

According to the deputy general Secretary of the European Trade Union Confederation, Per Hilmersson, “posted workers are often in a more vulnerable situation, given that they do not always speak the language of the host member state or are familiar with the legislation of that member state. Quite often they are not a member of a trade union, or unaware of their rights as workers and because of that they may experience abuse based on exploitative and illegal working conditions or fraudulent social security certificates”.

The battle in Brussels

During the last 20 years, hundreds of abuses and violations concerning the posting of workers have been documented throughout Europe, while dozens of cases have been brought before the European Court of Justice, demonstrating the need to further monitor posting not only at European, but also at a national level.

READ MORE

Fierce policy disputes surrounding the regulatory regime for posting have been taking place in the EU in recent years. These debates peaked around 2016 and it was no coincidence that the countries condemning the complications of the current relevant EU legislation, were mainly France, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, that were among the major receiving countries for posted workers. Indeed, in specific areas of these countries, and especially in sectors such as construction, the local workforce had been largely replaced by posted workers.

In the hard negotiations that took place, these countries, and especially France, made use of the argument of “social dumping”, the tackling of which had been declared a personal commitment by the former head of the EU Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker. Social dumping refers to the practice of offering wages much lower than normal in an industry, often to foreign workers brought in specifically for a job.

The “fruit” of the intra-European disputes, the latest European Directive (Directive 2018/957/EU ) was issued in 2018, amending the previous ones. It will have to be incorporated in national legislation across Europe by July 30, 2020 – in the heart of the next tourist season for Greece.

The new Directive aims to reinforce the legal protection of posted workers, including those that are posted through temporary agencies. It is also very precise and stipulates that posted workers should have the same wage and working conditions as the ones existing in their place of work, under the principle of “equal pay for equal work”.

“Fraudulent behavior through the posting of workers continues. We still need fairer rules for mobility and more effective enforcement, especially in cross-border situations”, notes Per Hilmersson, the deputy general Secretary of European Trade Union Confederation. The ETUC suggests that the imbalance on the EU internal market between economic freedoms and social rights, including workers’ and trade union rights, needs to be corrected through a “social protocol to the EU treaties stipulating that when in conflict, social rights will prevail”, he concludes.

ΕU: From the Bolkestein Directive to the European Labour Authority

The final text, approved by the European Parliament in late 2006, abolished the provision for the inclusion of workers, including those posted, in the legislation of the country of origin, which had provoked the most serious reactions.

The Bolkestein Directive was preceded by the European Directive 1996/71/EC on posted workers which was general and vague, stating that “the laws of the Member States must be coordinated in order to provide for a core of compulsory rules for minimum protection (of workers).”

This was followed by Directive 2014/67/EU, which contained regulations for the implementation of the 1996 Directive and the specialization of its provisions.

The third relevant European Directive 2018/957/EU, which was issued in June 2018 and must be incorporated into national legislation by 30 July 2020, amends the 1996 Directive aiming at “equal pay for equal work”, the basic motto of the EU concerning employee mobility.

The latest European act concerns the establishment of the European Labour Authority, which aims, as quoted “to improve access to information on rights and obligations in the areas of labour mobility and social security coordination, to strengthen cooperation between the authorities in the cross-border enforcement of relevant EU legislation, to facilitate, inter alia, the conduct of joint inspections.” The Authority started operating only in October 2019, has its headquarters in Bratislava, Slovakia, and an increasing annual funding, which in 2024 (when it is scheduled to be fully operational) will reach 50 million euros.

Τhe fertile ground of the Greek tourism sector

Auditing and protection are needed not only when it comes to posted workers’ rights across Europe, but also for all employees in the Greek tourism industry, which has seen a massive increase in visitor numbers, after the economic recession that Greece faced in 2008.

Approximately 33 million people visited the country in 2019, which now ranks among the most popular destinations in the world. The hotel, restaurant and all other businesses included in the tourism sector, fuel the greek economy, generating almost 31% of national GDP. Nevertheless, this economic growth doesn’t reflect on the labour force of the tourism sector, which in 2019 came close to 1 million employees.

For foreign employees recruited by Job Trust, like Anton, Daniela or Agnieszka, it is difficult to react and request improvement of working conditions or demand payment of overtime, mainly because they never signed an actual contract with the hotel itself. But even for local hotel employees, defending labour rights seems to be a continuous struggle.

The fact that Job Trust’s web of companies was able to operate unchecked for several years while tens of hotels were using its services and violating the rights of hundreds of foreign workers, should not be examined as a singular lapse in the authorities’ investigatory powers.

By talking to trade unionists, current and former hotel employees and overcoming the ingrained fear and hesitation that blankets the industry, and by obtaining and scrutinizing work contracts, we noted that we are in the middle of a deep transformation of the very nature of work in Greek hotels. A trend that leads to more precarity, dismantles all labour rights, bypasses the sectoral collective agreement, and creates deep insecurity. A trend slowly but efficiently eluding the celebratory headlines extolling the economic contribution of tourism, “Greece’s heavy industry”.

The exponential increase in contracting

More Greek hotels have been taking advantage of legislation imposed as part of the Greek bailout memoranda and have outsourced a large number of their employees to contractors and temporary employment agencies, with in-house workers becoming a minority in many cases.

“During joint audits that we performed in October with the Hellenic Labour Inspectorate, we discovered that in two newly-opened Athenian hotels only 7 out of 50 were hotel employees. The rest were employees of a cleaning and catering company set up by the owner of the hotel itself. 80% of the employees in both hotels were contract workers”, says Giorgos Stefanakis, president of the Attica branch of the Trade Union of Workers in Food and Tourism.

According to the president of the Panhellenic Federation of Tourism Employees, Giorgos Chotzoglou, “there have been many companies that provide hotels with employees in areas where there weren’t contract workers before. Up until a few years ago, there were contracts only for cleaning services. Now we see contracting in all job positions – waiters, cooks, bartenders”. Furthermore, Manolis Kamilakis, member of the Trade Union of Workers in Food and Tourism in Athens, explains: “To give you an example, twenty years ago 600 people were employed by a hotel, all on a permanent basis. Today, less than 200 would be full-time employees and all the rest would be either from contractors or have temporary contracts”.

Grigoris Tasios, the president of the Hellenic Hoteliers Federation, demonstrates as a cause of the existence or proliferation of workers’ companies, market conditions “that lead to other solutions (…) and that create the need for staff with another payroll”, while arguing that the main reason is the lack of employees, willing to work long-term in seasonal positions in the industry, where working hours and working days are often more intensive than in other occupations. Especially for foreign workers, the president of the Federation says that “from the moment they come to Greece, they know the money they are given and that is why they come. If the working conditions are problematic, of course the company is to blame, but as far as the salary is concerned, the employee knows beforehand. If the working conditions are not right, that’s another thing.

The inapplicable sectoral collective agreement

One of the main reasons for the exponential growth of contracting workers in greek hotels is the implementation in 2018 of the sectoral collective agreement. Contracting and outsourcing allows hotels to bypass the provisions of the agreement and therefore their legal obligations to employees.

READ MORE

“In a fully deregulated Greek labour market the tourism sector could not be an exception. In some cases, the practice of virtual recruitment to a business other than the tourism industry was also mentioned, in order to avoid compliance with the regulations of the sectoral collective agreement”, explains Apostolis Kapsalis , expert on labour relations. “It is clear that one of the reasons why contracting or third-party employment is selected, is to reduce wage costs and to break the principle of equal treatment in relation to other employees in a company. Our study shows that in tourism these flexible forms of employment cover about 10% of the sample workers and mainly waiters, cooks and bartenders.”

A thousand and one work contracts

Indicative is the case of a former workero in the prestigious Hilton Hotel in Athens, who had signed hundreds of contracts during his 1,5 year stint with its direct employer, the temporary employment agency “ISS Services”. He was called for a job interview at the premises of Hilton, but after that he was told to go to the offices of “ISS Services” for the hiring process. While working in Hilton (operated at that time in Greece by the consortium Home Holdings, with TEMES S.A. and D-Marine Investments Holding B.V. as shareholders) the employee, whose details remain at the disposal of our team, protested and sought to improve his work conditions. After that, the hotel and the contractor didn’t renew his contract, which, according to the employee, is equivalent to his dismissal.

As he characteristically put it, “I started working around Easter-time in 2017 until September 2018. The longest contract I signed during these 1,5 years was for 5 days. Hilton was announcing a weekly schedule and they changed it every week according to their needs. I would work 2-3 or 4-5 days each week, depending on the bookings. I worked first and then I signed the contracts once a week. My wage was far less than what in-house employees get for the exact same job as mine. People working at hotels, refer to the contracting companies as “sweat shops”.

The employee vividly describes the intensification of work: “It would be a miracle to have a break during the morning shift”, he says and adds that at night there were only two people to clean the common spaces of the hotel that occupy a large area as well as the rooms. “If someone protested, there would be “punishment “in the program with difficult shifts and fewer wages. There was an employee who was forced to work one day a week in order to resign. There is no dismissal, they just don’t need you anymore when your short-term contract ends.”

Multiple minimum day contracts

The aforementioned practice is lawful. According to Greek law, a worker can be employed on a temporary basis, and have its contract renewed, for a period of up to 36 months. For longer periods, the law stipulates that the contract automatically is converted to a permanent one. However, there’s a small window. If there’s an interval of 23 days between temporary employment periods, the 36-month “stopwatch” resets. Thus, an infinite number of 36-month temporary employment periods is possible, if 23 days pass between them. The minimum time required between permanent stints used to be around 42 days, but it was lessened in the last years of the economic crisis.

Responding to questions we sent, the Hilton hotel claims that “the remuneration and other working conditions of the employees of Hilton Athens are determined in accordance with the provisions of the applicable and binding collective bargaining agreement” and that “Hilton Athens complies with all the provisions of the law concerning the remuneration, leave and allowances of employees”. Corresponding is the response of the company ISS, which considers the description of the events inaccurate, emphasizing: “according to article 117 of Law 4052/2012 the transfer of an employee by the direct employer (EPA) to an indirect employer (including renewals) is allowed for a period up to 36 months. For staff granted to hotels, ISS either implements the sectoral collective agreement or the respective operational agreement implemented by the hotel, which provides for higher salaries than the sectoral agreement.”

A midsummer night’s nightmare

Cases like the above are ever-increasing in the Greek tourism industry, where a plethora of labour violations are registered each summer. However, the dominant media narrative is one of euphoria, over the increasing economic share of the industry in the Greek economy.

Our team, following the trails of Job Trust and its employees in the summer of 2019, traveled to Halkidiki, Crete, Santorini and Corfu. The working and living conditions for workers that are directly employed by hotels are not much better than the ones posted workers have to face. Stamatis Pelais, the president of the Corfu branch of the Trade Union of Workers in Food and Tourism describes: “In many hotels the living conditions for hotel employees are horrendous. There are people living in containers for 5-6 months, as long as the tourist season lasts”.

Some of the employees at the Atlantica Nissaki Beach hotel in Corfu live in the containers pictured above for the duration of the tourist season. The general manager of the hotel gave the following response to our question: “We believe that the living conditions of employees are tolerable (residence mainly for two persons per room, a private bathroom/shower with hot running water on a 24-hour basis, aircondition, wifi), but we wish to improve them. Our goal is to fully upgrade the living spaces of our employees within the next two years”.

A 21-year-old French student who worked for two months via STAFF Company at the Iberostar Creta Marine Hotel in Crete in 2019 describes a similar situation: “The living conditions were very bad, we lived in the hotel basement. The rooms were terribly damp and there were cockroaches and mosquitoes. In fact, five days before we left, due to a problem with the plumbing, the ceiling in my room collapsed”.

Images from the room of a French student, employee of a hotel in Crete.

Maud, from France, also worked via STAFF Company at the Iberostar Creta Panorama Hotel in Rethymno, but only for 5 days, as she could not stand the working and living conditions. “There were strict rules, we were not allowed to walk around the hotel facilities, nor to go to the pool or the beach. Every day we ate reheated spaghetti or potatoes”. Asked if she knew beforehand the conditions she would face, Maud replied: “Of course not, but the company knew, but it didn’t matter. They are ‘selling a dream’ to the candidates, until they arrive in Greece “.

Adam, the STAFF Company employee from the UK that worked in Elounda, recalls:“I had to adjust to the Greek way of working, you go home when you’ve finished work, and not when your shift has ended, which is what happens in the UK. A lot of the Greek nationals working didn’t have a single day off for the whole summer. I realised how difficult it must be for a single person to live in Greece if he/she doesn’t have any other kind of financial support”.

“No hotel employee works only for 40 hours a week. You start in the morning and you don’t know what time you will be finished, whether you will work overtime (always unpaid) or 7 days a week. There is also what the employees call ‘three-fold’: the shift splits 2 times during the day, morning, afternoon and night. The last few years accidents at work due to fatigue and intensification are heavily increasing”, says Stratos Maniavos, member of the Union of Hotel Employees in Rethymno, Crete.

Not only at Santorini and Crete, but at all the tourist destinations in Greece, hotel employees, local and posted, seem to be invisible to Greek authorities. The Greek Labour Inspectorate has been watered down the last few years. “There are 4 labour inspectors in Corfu for thousands of businessess. Sometimes the inspectors can’t perform an audit at a location outside of town, because they don’t have a car”, says Stamatis Pelais, the president of the local workers’ union. Stratos Maniavos describes the situation in Crete: “The labour inspectors -if and when they perform inspections- give out recommendations or maybe a small fine. Usually it is known when they’re headed for inspections and all the hoteliers are prepared.”

Lack of data and ignorance of those in charge

We tried to contact the Labour Inspectorate and the Greek Ministry of Labour & Social Affairs in order to get some answers on the working conditions of hotel employees and on posted workers. We formally and officially requested data regarding working conditions in tourism, the share of contractors in the industry, the number of foreign posted workers, the number of confirmed violations and their nature. Our team invoked the Presidential Decree 28/2015 concerning the right of access to public records. The answer we received was that the authorities don’t have assorted information on posting or contracting in every sector of the economy, and that they can only refer us to the official reports on the ministry’s website. We also submitted questions to the current minister of Labour, I. Vroutsis, the former Minister of Labour, ms. E. Ahtsioghlou and the Minister of Tourism, Ch. Theocharis, but did not receive a positive response to our request.

While contacting the Greek authorities, we realised that most of the labour inspectors didn’t have any knowledge on the posting procedures, and actually no one knew that a company based in Bulgaria has been posting dozens of employees in greek hotels for several years.

Our team’s insistent requests resulted in the opening of an official investigation of the Labour Inspectorate on STAFF Company and its posting procedures in Greece. Sources from the hotel industry that were summoned for inspection, confirm that the ongoing investigation focuses on the activity of STAFF Company.

Finally, we reached out to “Job Trust” and “Staff Company”. We sent a set of detailed questions to the private recruiting agency “Job Trust” in Thessaloniki. The director Irina Aslanov responded by stating that “the vague allegations to which you refer are completely unfounded and unsubstantial. We are unaware of the origin of these allegations and we have serious reasons to distrust the motives and therefore the credibility”, while at the same time stressing that she reserves the right to exercise all legal rights. And while she informs us that he is happy “for our research in the first place”, she considers our questions on the activity of Job Trust “essentially irrelevant to the research you conduct”.

Job Trust’s response

“First of all, we are happy for the subject of your research (working conditions in Greece, etc.), which concerns a very important sector of the Greek economy, with which our office has the pleasure of being directly related. You obviously are aware that our office is very successful in its field and enjoys a special reputation and appreciation for its organization, absolute consistency and high professionalism, as evidenced by the most undeniable fact that it has been a constant point of reference for many years and throughout Greece, both for prospective employees and for top hotels – pillars of Greek tourism.

We will not hesitate to assure you that, during our broad and longtime activity, we are occasionally confronted with individual cases of sometimes justified and sometimes unjustified dissatisfaction, either on the part of employees or employers. We consider such incidents inevitable and you can be sure that our office has always approached them, all without exception, with due care and severity, as befits its prestige and position in the Greek market, always looking for the best solution.

We would also like to inform you that recently we have become aware of fabricated and completely directed, from specific sources, false complaints against our office. In this context there are even cases – if you do not already know about them – where the so-called complainants are encouraged from journalists to file complaints against us by simply completing pre-printed complaint texts. You obviously understand that these are very serious wrongdoings, for which we are already in contact with the competent authorities.

In view of all the above, therefore, allow us to oppose the vague allegations to which you refer as completely unfounded and unsubstantial, We are unaware of the origin of these allegations and we have serious reasons to distrust the motives and therefore the credibility. The same goes for the rest of your questions, which – as essentially irrelevant to the subject of your research in the first place, give us the feeling, unfortunately, that they are part of a similar effort to target our office.

We reserve the right to exercise any of our legal rights, including for compensation for infringing on the reputation and prestige of our office.”

Job Trust,

Irina Aslanov, Director”

We sent questions via email to STAFF Company at the only contact address of the company, the email of “Omega”, the accounting office listed as a point of contact for the Bulgarian authorities. As there was no response, we contacted the office by phone to receive the answer that we had to send our questions to the email “[email protected]” of the company Job Trust. We followed this suggestion, however we did not receive any response from Alexandros Savvidis, the director and owner of the Bulgarian company.

We followed the same process of sending questions to the at least 32 hotels that we know collaborated with Job Trust and STAFF Company in the summer of 2019. Apart from general assurances that the hotels comply with labour law, we have not received any other response regarding their cooperation with the specific companies.

Low salaries, high earnings

Apart from the Bulgarian prosecutors’ mention in the case of an employee who was insured for a sum significantly less than the already low real wage, it was proven impossible, during our investigation in Bulgaria, to retrieve accurate information on the exact social security contributions paid by STAFF Company for the employees that were posted in Greek hotels during the summer season of 2019. Were Adam, Agnieszka, Vlad, Daniela and the rest of the workers registered for every single day they worked? Was Vlad declared as an employee for 30 consecutive days of work in September or Agnieszka for 6 days of work a week?

READ MORE

Non-wage costs differ in Bulgaria, compared to Greece. In Bulgaria, the non-wage cost is approximately 16,2% while in Greece this percentage is around 22%.

Apart from the social security related issues, there are also questions on corporate taxation and the risks of tax avoidance. After the 2004 and 2007 Eastern enlargement of the EU, thousands of Greeks relocated their businesses to nearby balkan countries and especially to neighbouring Bulgaria, making Greece one of the largest investors in the country. Thousands of active companies are now registered in Bulgaria but are operated by Greeks. The Bulgarian company flat-rate tax of 10% is much more appealing compared to the company tax of 29% that is in effect in Greece.

As shown on the balance sheets of the numerous companies of Alexandros Savvidis in Bulgaria, he generates an annual total revenue of over 2 million lev (approx. 1 million euro) the last 3 years. The revenue from services provided to foreign customers make up 76-98% of the total revenue. Are these clients based in Bulgaria or in Greece? Does the actual substantive and genuine economic activity and value creation take place in Bulgaria or in Greece? Are taxes paid in the jurisdictions where the economic activity takes place, as it is stated in the European Parliament resolution of 26 March 2019 on financial crimes, tax evasion and tax avoidance?

Various ways of abuses related to posting of workers have been reported across the EU. “Typically, the posting of workers is abused by employers aiming to evade taxes by declaring one remuneration rate (typically the minimum required) in the receiving member state but actually paying out and paying taxes on another (often even lower) rate in the country of origin. As the number of posted workers has risen in the past decade, controlling such cases has become increasingly difficult, as it requires state of the art risk assessment and coordination between labour authorities in member states. Scrutiny is further prevented by the easing of the establishment of temporary work agencies or letterbox companies, which then are closed down before authorities can check on them. In addition, the authorities usually cannot control whether the declared employment matches the actual work schedule of posted workers in the other Member State. It should also be noted that such practices are often accompanied by disregard for the workers’ human and labour rights, such as withholding part of their salaries as accommodation and subsistence fees, exceeding the maximum official working hours per day, etc”, as it is noted on a report by the Bulgarian Center for the Study of Democracy Group, that was published in 2018 as part of the European Platform for Undeclared Work.

The next tourist season begins

As Alexandros Savvidis, Irina Aslanov, Job Trust and their numerous companies are getting ready for the summer season of 2020, dozens of students and job seekers across Europe are fascinated by the description of dream jobs in hotels in Greece: the promise of a higher pay for Eastern Europeans, compared to the very low basic salary in their home countries, the sunny beaches and the warm climate for Western Europeans, the potential chance to learn and be trained for students, the hope of an exciting and memorable experience for all. Will there also be overworked, underpaid and underdeclared employees in dozens greek hotels this year?

In the meantime, Adam, Agnieszka, Vlad, Daniela and many other posted workers will try to forget about the summer of 2019. “It was a prison with no escape”, says Agnieszka, while Adam remembers, “I feel so as I was often working longer hours than stated. I wasn’t getting all of my meals. I lost a lot of weight and became fatigued. I felt I was lost in paradise”.

Santorini: The Greek tourism industry’s very own Eldorado

From afar, the island’s imposing cliffs, as seen from ships slowly approaching the Caldera, conceal the chaotic procession of crowds flooding the Santorini streets. The traffic caused on the island by this super-tourism makes one think more of central London, rather than a small island of the Cycladic complex.

Today, Santorini is one of the ‘blue chips’ of Greek tourism. A globally recognizable and widely advertised brand name, it is one of the most popular and expensive destinations in Greece, with hundreds of thousands of visitors each summer. The island dominates the headlines worldwide as a tourism success story, attracting visitors from Asia and India, diversifying its traditional European and North American tourism markets.

However, there is one phenomenon that is often overlooked in journalistic accounts of the island: working conditions for employees are inversely proportional to the luxury offered to customers. The large workforce serving the island’s millions of visitors is facing on the one hand the intensification of its labour and on the other lack of housing, as Santorini is facing an acute housing crisis – even the island’s teachers and doctors have been reported to be forced to sleep in tents, in their cars or even in sleeping bags.

Accommodation, when provided by employers, often appears to be transformed into a tool for intimidating employees who are at risk of being left homeless in the event of a labour dispute. As Dimitris Kamzelas, vice president of the Union of Food-Tourism and Associated Professions of Thira stated, “when your room depends on the business you work, you don’t talk back at all. And if your boss attacks you verbally, you won’t react. If you do, you have to leave the business and therefore the island”.

However, employer-provided accommodation is not only unsuitable for living, but often proves to be dangerous to employees’ health. Fotini, a former employee of one of the largest hotels in Santorini, describes: “You were never allowed to sit or take a break. I was staying in a small room in the basement without a window and with a cracked ceiling. The bathroom did not have ventilation. We were not allowed to make coffee, we had to pay even for that.”

Indicative is the account of Vangelis, a worker on the island who had to secure his own accommodation: “We live 3-4 persons together in a single room with walls cracked from mold. What they are doing is taking a house, dividing it into three and charging 200 euros per head. The first year I came to work here, I shared a very small room with another worker and we paid 500 euros. We didn’t even have a toilet; we didn’t have anything”.

Behind the success story

In addition to the housing issue, which is not at all innocent, Fotini explains: “I had to work in the reception, clean the rooms and wash dishes in the kitchen, if necessary. I worked 7 days a week for 10-11 hours per day, without allowances or overtime pay. The salary was 1,200 euros, of which 854.16 was in the books and the rest was cash in hand”.

The intensified work schedule seriously adds to the deterioration of the mental and physical health of the island’s workforce. According to Alket Yakim, a member of the Tourism and Hospitality trade union of Thira, “when you work like this, even when you finish your shift, you can never fully relax. You sit with others, but you’re not really there. You become irritable”. As he confided to us, if the current trend does not change and labour rights violations continue unabated, he will probably become one of the many who do not return to work on this island.

The workers, the infrastructure of Santorini and the wider community of the island face what is coming to be known as hyper-tourism, under the shadow of one of the biggest “success stories” of the Greek tourism industry, perhaps counting down the days until their own volcanic eruption.

By Lina Kapetaniou and Elvira Krithari, Ioanna Louloudi, Ilias Stathatos, members of MIIR. Additional reporting in Bulgaria by Stanimir Vaglenov and in Romania by Timea Hont.

The investigation was published in a special section in the “Efimerida ton Syntakton” newspaper on Saturday, March 14, 2020. Part of the investigation was also published in Romania’s “Libertatea” newspaper.

This investigative project has been carried out with the support of iMEdD. The views, data and opinions presented in this article do not necessarily coincide with iMEdD’s views, data and opinions.

Graphics were produced by Eugenios Kalofolias. The motion graphics video was produced with the cooperation of Alexia Barakou (art direction, motion graphics) and Alexis Koukias-Pantelis (sound design).

If you have been employed through a private employment agency in the tourism sector or other sectors of the Greek economy and you would like to share your experience with us, don’t hesitate to contact our team by sending us an email at [email protected].

Υποστηρίξτε το MIIR

Η ερευνητική δημοσιογραφία χωρίς εξαρτήσεις ή διαφημίσεις χρειάζεται υλικούς πόρους και αρκετό χρόνο.

Βοηθήστε μας να συνεχίσουμε.

IBAN: GR08 0140 1040 1040 0200 2028 234 (Alpha Bank)